To our Wonder of Parenting podcast, a mom wrote two questions that we are asked a great deal. “Are some kids just more resilient than others? I have three children, two girls and one boy. I think I’m doing all the right things to make sure they are resilient but how can I be sure?”

A dad wrote about his daughter and son, four and five. “We’ve noticed our daughter is having trouble standing up for herself. Our son is more aggressive by nature, but he can melt to mush when he loses at a game. I think my son is more naturally resilient than my daughter, but my wife says just the opposite. We want to know if we are raising resilient kids.”

A new school semester (February 2022) has started under complex circumstances. Our children watch us carefully, seeing our fear of Covid disease and/or our fear of Covid vaccines. These children have lived in fear-constancy for almost two years whether behind masks and screens, or otherwise socially isolated.

As we noted in the first essay of this series, constant fear and social isolation, like any repeated traumas, can take their toll, potentially rewiring the brain. My first essay in this Resilience series (see https://gurianinstitute.com/building-resilience-in-american-children-part-i-ending-their-covid-fear/) dealt specifically with removing Covid fear from children’s lives to protect their development of resilience.

Meanwhile, as the two parents indicated, issues around children and resilience have a universal place in adult concern predating Covid-19 and sure to follow us into our “post-covid” world. If our family, community, and civilization is to survive and thrive, we need our children to become resilient teens and adults. But is there a single trait called “resilience” we discover by reaching into a child’s mind and saying, “Ah, there we go, that’s it!”

Like everything involving childhood, resilience occurs on a spectrum. When comparing dozens, hundreds, thousand, millions of children we see the spectrum clearly, like the parents did who began this essay, with some kids more naturally resilience than others, some kids nurtured toward resilience more than others, some kids curated by their cultures toward more resilience than others. The parents were asking spectrum questions in the same way we do about every aspect of a child’s life–eyesight, running speed, facial features, eye-hand-coordination, fast twitch muscles, extroversion/introversion, hearing, intelligence, and so on. Whatever your child’s position on a gene expression spectrum, you, your school, and your community can nurture the nature of that child.

The Natural Journey of Resilience Building

Over the winter break, I re-read Killing Floor, the debut novel by Edgar Award winning author Lee Child (1996). Jack Reacher, an ex-Army MP, wanders into a Georgia town, Margrave, that needs his help. Bad things are happening and they keep getting worse every day. Part way into the novel, a local cop, Roscoe, and Reacher are targeted for murder. They escape death and torture by coincidence–spontaneously leaving Roscoe’s home for a romantic getaway in a motel down the highway. When Roscoe and Reacher come back to town the next morning, they see Roscoe’s front door broken and four sets of boot-prints, the same prints seen in another house where the husband and wife were tortured and murdered two days before.

“Roscoe shuddered. Pushed herself into the corner by the door. Tried to flatten herself onto the wall. Stared into space like she was seeing all the nameless horrors.” As she starts to go into shock and cries, Reacher narrates, “I knew I had to sound confident. Fear would not get her anywhere. Fear would just sap her energy. She had to face it down.” Reacher problem-solves in his head then provides her with a potential plan. “I said it with total certainty. Total conviction. Like absolutely no other possibility existed. I wanted Roscoe to feel safe. I wanted to give her that. I didn’t want her to feel afraid.” Roscoe listens to his plan then pushes her hair back, dries her tears, and “put on a brave smile. The crisis was gone. She was back up and running.”

Lee Child’s novels are page-turner thrillers. They also include what nearly every good book includes: a tacit study of the journey of resilience. The lead characters exist on a resilience spectrum we can notice if we are looking for it. Think of the Bible, ancient mythology, the Qur’an, the Upanishads; think of novels by Stephen King, Dean Koontz, PD James, Danielle Steele, John Sandford, Linda Howard, George R.R. Martin, Robert Jordan, Donna Tartt, Anthony Doerr. The list is endless: whatever genre you like to read, you’ll see a fear/resilience narrative like Reacher and Roscoe face. In my 2007 The Purpose of Boys, I analyzed novels, videogames, films, children’s books too; the primal cycle and the resilience spectrum is in all literature. After publishing my young adult novel The Stone Boys (2019) I saw the cycle in this novel, though I was not conscious of writing it into the plot while crafting the book.

The Nature of Resilience

The fear/resilience cycle exists in human narratives because it is foundational to human growth. Nature, nurture, and culture are the trinity of primary drivers in child development and they begin with nature. All children have their own genetic baseline–nature–on the resilience spectrum that comes from gene structures inherited from mom’s and dad’s genetic lines. In Child’s novel, it becomes obvious that Reacher has the most inherited, genetic resilience, while Roscoe and Finlay (her boss, the Chief of Detectives) have the next most on the spectrum, and a character named Paul Hubble, who withdraws into a shell when challenged, has perhaps the least natural resilience on the spectrum.

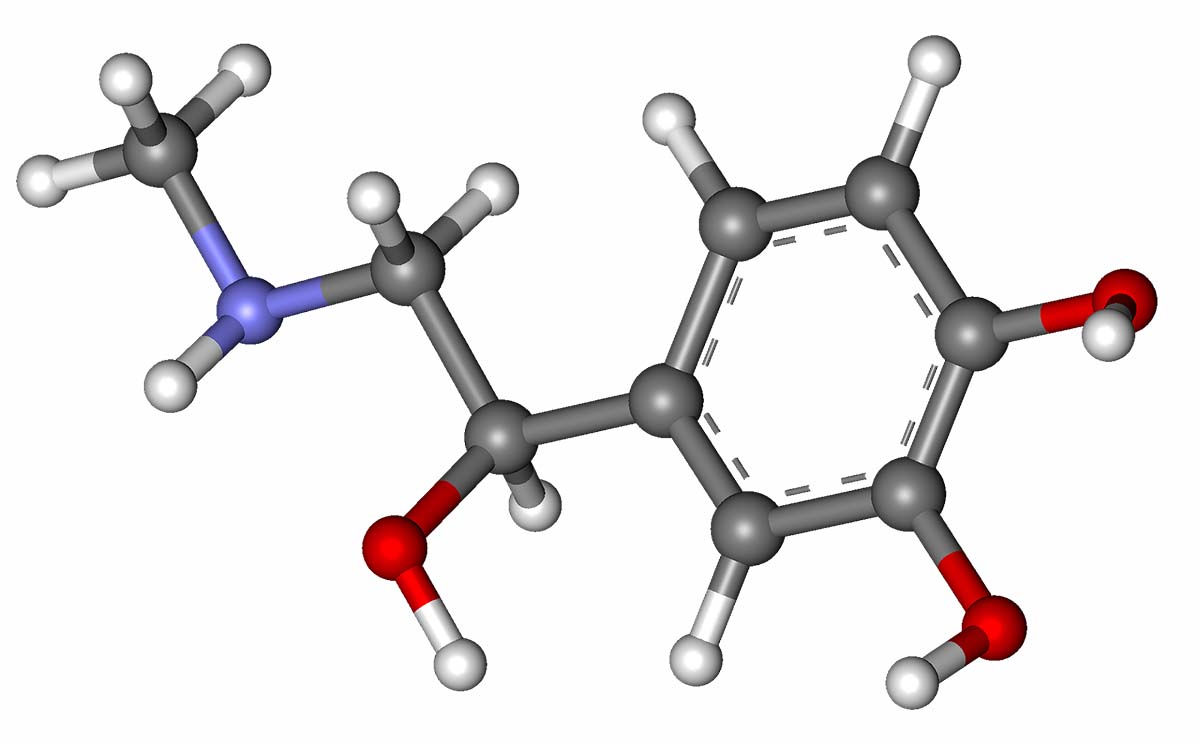

Were these three people real and alive we could bring them into a genetics lab and look at these resilience-bearing assets in their bloodstreams and brains:

*OPRMI cells and proteins

*5 HTT chromosome markers

*Susceptibility loci at DCLK2, KLHL36, and SLC15A5

*COMT (catechol-O-methyltransferase) genes

*Serotonin transporter gene activity (SLC6A4)

*Neuropeptide Y (NPY).

Because of the successful (and ongoing) genome mapping of 2003 – 2004, we learn more about our own genes every day. Here are three studies you can access immediately on google for a glimpse into the genes and markers I just noted (this is not an exhaustive list):

“Genome-wide analyses of psychological resilience in U.S. Army soldiers.” Stein MB, Choi KW, Jain S, Campbell-Sills L, Chen CY, Gelernter J, He F, Heeringa SG, Maihofer AX, Nievergelt C, Nock MK, Ripke S, Sun X, Kessler RC, Smoller JW, Ursano RJ. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2019 Jul;180(5):310-319. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32730. Epub 2019 May 13. PMID: 31081985 Free PMC article.

“Genetics of resilience: Implications from genome-wide association studies and candidate genes of the stress response system in post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.” Stephan Maul, Ian Giegling, Chiara Fabbri, Filippo Corponi, Alessandro Serretti, Dan Rujescu. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2020 Mar;183(2):77-94. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32763. Epub 2019 Oct 4.

“The Genetics of Stress-Related Disorders: PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety Disorders.” Smoller JW. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016 Jan;41(1):297-319. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.266. Epub 2015 Aug 31. PMID: 26321314.

The language in these studies is academic, clinical, and sometimes hard for a layperson to read, but I include them because I think they will be available online for some time, and because I believe there is joy in every parent becoming a citizen scientist. In this essay, I’ll refer back to essential points we can learn from these studies and others like them to help you in that citizenry and that quest. Meanwhile, as we discuss genetics and inherited traits, please keep two caveats in mind.

First, anything we say about genes is necessarily said in a vacuum–we have to isolate variables to talk about them because we cannot talk about a hundred related issues at the same time, which means our analysis can imply absolute value when it should remain more a direction, glimpse, or trace of insight to be built upon. It is always crucial we do not consider one sentence about biology to connote destiny. Rather, biology is proclivity, it is measurable tendency. The proclivity and tendency are what I mean when I use the word nature in the genetic context. We each bring our genes to nurture and culture (subjects of our third and fourth essays) for testing and refining.

That whole caveat notwithstanding, though, knowing the gene-based and natural tendencies in our children is very useful because natural laws do apply to child-raising as they apply to everything else.

The Science of Crying Is Not Necessarily the Science of Resilience

The second caveat is this: understanding resilience genetics will not mean starting with or ending with “you see, resilient people don’t cry.” In the scene I quoted a moment ago, Roscoe cried and Reacher did not. Should we say Roscoe is not resilient because she cried? Or Reacher’s lack of tears prove his superiority in resilience? No. More often than not, crying behavior does not display entrenched fragility.

This is important to know for many reasons not the least of which is biological sex difference in crying. If we were to connect crying with fragility and lack of resilience, we would just decide women are fragile and weak (i.e. not resilient) and men are more naturally resilient. This is an old stereotype that has never been true and does not fit science or natural law. Men who don’t cry can be very fragile and lack resilience; women who do cry can be quite resilient. The damaging stereotype is a distorted connection of two different biological baselines.

One baseline is that, by nature, girls and women cry more tears than boys and men on average. This, of course, is obvious to everyone once puberty hits. The biological underpinning for this sex difference is mainly the higher levels of prolactin in female bloodstreams. Prolacton promotes breast and tear glad production. Lacking the high amounts of this chemical, males have flatter chests, smaller tear glands, and wider tear ducts. You will have noticed that when adolescent and adult men do cry, they tend to brim tears above the eyelids; girls and women tend to drop more tears down their cheeks and produce more tears in their glands.

As with all biological science, there are exceptions (men who cry more tears than women), but the exceptions are rare enough to prove the rule. But genes for tear gland production are not resilience genetics. A “crier” can be very high in the resilience genetics I listed earlier, thus high on the resilience spectrum; and crying can be functional for resilience rather than “weakness” as it can return someone to equilibrium quickly, as it does Roscoe who cries in the face of the immediate trauma then, having processed the fear and trauma, resets toward a resilient set of next steps. Reacher, also resilient, processes trauma in a more male-specific way: fewer tears, more problem-solving, delayed emotional reaction, then later in his story, toward the end of the novel, when lots of emotions catch up to him, he does cry in his way with eyes brimming on ear but dropping down his cheek.

Let’s agree, then, that crying does not necessarily mean weakness or lack of fragility, but can the old stereotype ring true in some way? It can fit if we alter it to these sign of fragility, “weakness”, or lack of resilience:

- If the crying behavior distends significantly longer than needed–especially if the crier has a pattern of not returning appropriately to equilibrium.

- If the crying is actually whining which often goes beyond emotion-processing to manipulative behavior that weakens the psyche.

- If the crying behavior often occurs in ways that do not seem objectively appropriate to the actual situation.

Overall, however, crying behavior does not necessarily reveal resilience genetics in your child, so what does?

Building a Helpful Science of Resilience

George A. Bonanno, professor of psychology and director of the Loss, Trauma and Emotion Lab at Teachers College at Columbia published The End of Trauma in 2021. This is a very good read in which he provides three characteristics resilient people tend to show.

- A flexibility mindset (adaptability, flow with circumstances, problem-solving through difficulties).

- Some optimism rather than significant pessimism (faith and belief in self, general trust of the world even when the world has not shown itself to be utterly trustworthy).

- Challenge orientation (using challenge as a significant baseline for personal development rather than expecting escape-from-adversity as an entitlement).

Let’s say you have two children, 4 and 5. Which one might have more of a flexibility mindset? More optimism? Feels to you to be more “challenge-welcoming”? If you have a child with more of all three characteristics than other children, you are likely seeing the genetics of resilience budding through somewhat easily: this child’s genetics include higher resilience on the resilience spectrum than another child has. If you just see one characteristic, it might not be enough for a conclusion of any kind. And of course, 4 and 5 are young ages–a lot of brain growth and personality development is yet to come.

So let’s move to children 9 and 11. By these ages, there has been more gene expression and more brain development. How do the three characteristics appear in these children?

And what about children 13, 15, and 17—a lot more gene expression has occurred by now, puberty is flowing, the brains have developed even more: what do you see now?

To aid your study, revisit the journal you developed for our first essay or please take out a new sheaf of paper or open a new journal document on your computer. On it, list Bonanno’s three traits on the left then put a number scale for each on the right (1 through 10 with 1 the lowest and 10 the highest), then ask yourself what number on the scale/spectrum best reflects each trait in each of your children. Get help with this by talking to others around you like your own parents, other relatives, teachers, coaches, friends, colleagues who know your children and, thus, possess conscious or unconscious awareness of the child’s gene expression. Ask what of the three Bonanno characteristics they see in your child.

Now add to your page or create a new page for these three further characteristics of resilience my own research has revealed.

- Goal setting and task completion (the child sets goals, commits, self-motivates, follows through–not in every case, but as a general pattern).

- Rumination loop completion (experiences, expresses, then expels necessary emotions and curtails excessive, debilitating rumination).

- Accepts separation, rejection, and abandonment in a normal range (experiences the pain of each one, as every human being does, but has internal devices for returning to equilibrium).

As you are doing with Dr. Bonanno’s three characteristics, study your child for these three, as well, by using the scale of 1 to 10 with 1 being lowest and 10 highest. If your child has ADD, your child may naturally get more easily distracted than another child where goal setting is concerned but still, you should be able to observe where your child fits on a goal setting spectrum. And since genes are constantly expressing themselves throughout the lifespan of the child, goal setting and task completion can also mature naturally and individually in your child.

In a similar vein, ask yourself and others around you whether your child tends to move through emotive experiences back to equilibrium then problem-solving pretty quickly (this is what we mean by “rumination loop completion”) or stays hooked in rumination (“stuck”) for hours, days, or more. If your child has a depressive or social anxiety disorder, your child might be involved in excessive rumination to the point of mental health debilitation, and part of this child’s healing will involve working on completing rumination loops rather than remaining inside them for a long time.

Nearly every child will feel the pain of separation, rejection, and abandonment (e.g. on the day the child is left at preschool by parents), so there is a range of normal for all children that may be unrelated per se to resilience genetics, but resilience genetics do apply to abnormal reactions in this area. You can get help from others around you to study your child over a period of time; look for overreaction to normal rejection experiences. The 1 on the scale would indicate the most negative reactions to rejection and loss of the safe situation and the 10 would indicate the least reactivity or quickest return to equilibrium after the separation.

A Trauma Case Study

The 7th potential characteristic of resilience genetics I hope you’ll study is trauma-response. To begin, observe two children around you (or two adults) who suffered similar trauma. You will likely find that the same trauma can affect these various children differently even when the children are raised in the same home under the same circumstances. The studies I listed earlier and hundreds more you can access on google use this trauma-based lens to study the resilience spectrum inside us.

Brittany and Karrie were both sexually abused at the age of nine. The abuse trauma caused Karrie to spiral downward in adolescence with suicide attempts and drug and alcohol abuse then, finally, suicide. Brittany did not experience the same adolescent or adult downward spiral. In terms of a study control, during middle adolescence, both girls received therapy, and both girls’ family systems were relatively stable. Why the difference in life-course?

There are many interrelated reasons for it, we know, but the two girls’ genetics are a significant reason. Brittany tests higher (between 7 and 8) on the resilience spectrum for six out of the seven characteristics. She has a more resilience-positive genetic structure, thus possesses significant internal assets for surviving and thriving throughout and after trauma that Karrie, who tests at 3 to 4 on nearly all seven traits, does not possess.

I have chosen sexual abuse as the trauma to exemplify here in part because I am a survivor of childhood sexual abuse (see Saving Our Sons and The Stone Boys). My abuse trauma occurred over a six month period when I was ten. I struggled to heal that abuse trauma in therapy beginning in late adolescence; meanwhile, I did not spiral as many similar survivors around me have and do. I began working at age 16, achieved, performed, completed tasks, then later married, raised a family, and developed a career. I did not meet the fate that Karrie did.

When I use the seven traits to study where my genes fit on the resilience spectrum, my self-test looks like this:

Flexibility mindset — 4

Optimism — 8

Challenge Orientation– 9

Goal Setting/Achievement– 8

Rumination Loop Completion– 7

Abandonment/Separation– 7

Trauma Response– 7

Because this is merely a self-test, I have intrinsic bias and may have made some adjustment errors, but I checked the test with Gail, my wife of 36 years and a marriage and family therapist for forty. She basically corroborates this score. While the score does not reveal that I am the most resilient person in the world, it does show that I am scaling higher than some others on the natural resilience spectrum. In fact, I do have good genes for resilience in 5 HTT, OPRMI, and others that have helped me in my life, and helped the people around me over the years to nurture me toward resilience.

I hope you’ll take time to measure all 7 traits for all your children. Within the next decade, I believe gene research will become even more accessible to families so that your children will be able to assess their children’s genetics without needing to use observational and longitudinal tools such as the Seven Traits tool. But for now, this tool is much of what we have available.

I can report that in thirty-two years of working with counseling clients clinically, I have used versions of this tool to help many of them complete anecdotal analysis of their own genes on the resilience spectrum. Some clients who suffered less trauma than others spiraled terribly after the trauma. Their resilience spectrum scores, not surprisingly, were at the low end. Knowing this helped me tailor therapy to them.

How Can Knowledge of Genes Help You and Your Child?

This is a key takeaway from genetics research. Every parent and professional can hold up a mirror to the child to help us understand what this child needs, what your child needs. Some things you are doing as a parent with one child don’t work with others. Some things you do with one child you don’t need to do with others; these parental actions might actually push the other child in the wrong direction. Some things you do seem to be working with one child or all children yet you suspect your children aren’t growing up as resilient as you would like them to be. Knowing more of each child’s nature can help parents and adults mobilize all assets each child needs.

At a gut level, you are probably already doing some of this customization. Laurent might become immensely withdrawn because of traumatic nightmares, but Julie might take them in stride. You know you don’t need to treat nightmares in exactly the same way for each of them. Trent might self-isolate when bullied while his sister Grace plans out how to fight back. Cory needs more help from you in social interactions—more encouragement to make social connections—while Jenny generally does not. In fact, Jenny feels smothered by you much more than Cory, who might feel abandoned by you if you don’t help soothe the fear of rejection he is experiencing.

We worry least as parents, teachers, and caregivers when we know we are giving each child what they most need.

The Essential Questions Citizen Science Tool

Return if you will to the journal and continue it now (or please create one if you haven’t already); add to the Seven Traits tool a new page with the following essential questions for each child. To get a good baseline for each child, do this or some part of it every day or as often as you can for one or more months. (I will use “my child” in posing these questions, but you can apply them to any child in your care).

- Where do I think my child fits on the resilience spectrum from a genetic standpoint? What is my “proof” of where s/he stands? (The seven characteristics above can help answer these questions).

- When did my child have an opportunity to be resilient but chose against it? Why do I think my child choose against resilience? (List specific incidents and analyze your child and yourself within each incident).

- In what ways have I (or another parent, teacher, caregiver) assisted my child even if inadvertently in choosing against resilience-building, i.e. in what ways have I/we enabled a lack of resilience? (This may require some discussion between you and others, and I will give you more help on this and all these questions in a moment).

- What daily situations should I/we now choose for my child that will nurture more resilience? (If your child is a tween or teen, you can analyze this question with him/her as a family project).

- What daily activities are my children involved in that make them less resilient i.e., which activities seem to create less resilience in them? (Drugs, alcohol, porn use, excessive screen time will likely fit here and you may notice others).

The First Set of Essential Questions

To answer the first set, ask yourself and your children where they think they fit (if they are old enough for the conversation), and ask others in the family what they think about each child. As you have this conversation, ask yourself (and others), “Who does this child take after?” Identify the person or people your child takes after in a certain trait (optimism, trauma response, etc.), then get these “gene providers” to talk about the pros and cons of their own genetics with you and, if appropriate, your child. Then go deeper with these gene providers. Ask which of their own needs they wished their parents would have focused on during their upbringing.

“I think I was more fragile than my mom realized,” you yourself might say to your child in talking about this. “You’re kind of like me, sweetheart, and I’m not going to treat you like you are made of stone when you may need more praise or encouragement from me.”

Engage everyone you can in your child’s biological inheritance system so that “If grandpa Joe is like my child,” you might think, “I want to use him as an asset because, even if only unconsciously to this point, he knows what works and what doesn’t work for this set of genes.”

The Second Set of Essential Questions

With answers to the first questions in hand, you can answer the second set; this set helps you form a plan for the child. If your child is high in resilience genetics, you might say, “It’s okay that Sara wants to quit piano now–look at these other five opportunities in which she excels–I don’t have to keep forcing piano on her.” Or: “Brandon can give up piano, which he is complaining about, because he already follows through on commitments via sports, homework, chores, and family time.”

But if your child is lower in resilience by nature, you might insist on one or more activities that build resilience (like sports, which I’ll look at with you in a moment). “Alex is quitting everything, that’s no good, we have to get him off screens and into two physical activities per day.”

Or: “Lacey ruminates way too much about every little slight, so we need to talk with her about how to move to the problem-solving phase more quickly. Honey, I will take on that discussion during week days, and how about you do it on weekends? Let’s do this for two weeks then check in on how she is doing.”

As always, if your children are old enough to discuss all this with you, use your journal to help discuss what they each need. “Trace, look at this survey instrument we completed. What do you notice in it? What are two things you can choose that will help you become stronger? How about martial arts–could that be a good activity for you?”

“Tammy, you let people walk all over you—I was (am) this way and it’s not a great trait. Here’s how you can choose strength. I’ve had to learn this and I did it this way.” Then tell your story and use it to set up a plan for Tammy.

The Third Set of Essential Questions

As and after you answer the first two sets of questions you can engage in the third. This set doubles down on self-assessment. Answering these questions, perhaps now you’ll say to your child, “I think I intervene too much in your rough and tumble play. You’re not getting hurt, so I need to back off from that.” Perhaps your child, in turn, might say, “Yeah, it felt weird when you _______________, but please don’t stop doing _________________. I need that.”

Let’s say your child overuses recreational tech–video games, social media, You Tube, and devices. “Claire, too much screen time diminishes resilience-building, here’s the evidence. I’ve self-assessed and I see that I overuse it, too, which enables you too much toward screens. Let’s now list five activities that are healthier for you, fun for you, and/or sacred work for you (e.g. playing outside, more family time without devices, doing family chores, helping me fix the car, helping me cook).”

Claire might balk, but you keep going. “Since your brain development is at stake and you will become less resilient the more the time you spend on social media we’re going to spend the next month off social media and doing more of these other activities, then see what happens.”

This kind of intervention will likely be necessary especially if you have assessed via the first two sets of questions that your child leans toward less natural resilience on the resilience spectrum. The less resilient the child naturally is, the more risk of damage to the child’s psyche from overuse of tech, devices, social media, and screens.

The Fourth Set of Essential Questions

To help answer the fourth set of questions you might look at sports for help. Sports usually and naturally create resilience-development pathways for children in a number of ways.

- Mentors, coaches, and other children pro-socially encourage resilience and yet, too, often coerce children toward resilience. Both approaches are good ones. As Patricia Hawley at Texas Tech has presented in her child development studies (see more analysis and application of her research in Saving Our Sons and The Minds of Girls and in the third upcoming essay), coercive nurturance can be just as effective as cooperative or prosocial nurturance in building a resilient child. When the “coercive” becomes abuse, we put a stop to it, but coercive nurturance is generally not abuse.

- The physicality of the sports requires the healthy acceptance of pain and discomfort–children must fight through pain and discomfort toward service, performance, teamwork, and resilience.

- Social anxieties can sometimes dissipate via the constant contact of a sport. By your children constantly “being with” others in the athletics or sport, they are involved in what we call co-regulation. This is a process by which children hone their self-regulation skills by interacting with other co-regulators (other children and adults). Sports are high-dopamine activities (rewarding in the brain) that provide constant co-regulation.

- The brain increases self-esteem, self-worth, and a sense of purpose and service as the body accomplishes and performs in the sport. In the sport, too, especially at tween age and beyond, praise is generally held back unless deserved. Praise, thus, aligns with accomplishment. This is a good things because blanket praise does not tend to build resilience but praise connected to performance does.

For the child who is resistant to playing any team sports, a somewhat solo sport like climbing or tennis might be a good fit. When sports are not a good fit, the four elements of sports I just listed should still help you to ascertain other activities your child might like that do the same. During my upbringing, my friends and I weren’t good at sports so we gravitated toward chess, debate, orchestra, and other “nerdy” activities. Chess and debate were not physically painful like sports were but they were painful mentally and emotionally; thus, like sports, they pushed us further into resilience every day.

The Fifth Set of Essential Questions

To answer the fifth question you may need to look again at tech, devices, and screen time even more closely now.

We give our kids devices for constant use and dependency without realizing these devices algorithmically induce children toward more rumination, fear, anxiety, depression, and rage–all of which can mitigate resilience building. Even children we are sure started out very resilient can seem to us, after eight hours in front of a screen per day, immature, self-absorbed, purpose-less, and weakened.

Part of why this happens is the instant gratification that debilitates natural reward (dopamine) system development in the brain. As gratification becomes a child’s primary goal, resilience weakens. Each time your child immediately responds to a social media post with shame or inadequacy, resilience is affected.

If overuse of screens and social media is not an enemy of resilience-building, it is at least not friendly to the cause.

The Second Major Change We Must Make in American Childhood: Alter Parenting Toward Resilience as the Primary Goal

Studying our children can have implications for the goal-setting we do in every aspect of child-raising, so it is a useful exercise to ask: “Can we now go forward answering all or nearly all of our questions about child-raising with resilience-building as a childhood’s primary goal?” Our third essay will go deeply into a positive “Yes” answer to this question, but let me challenge us here to think about what it might mean to lift customization of parenting toward natural resilience to the top of the parenting and educational goal-chain.

Might resilience-building customized for each child give us a target for child-raising that includes other parenting goals like mental health, academic success, athletic performance, self-esteem building, empathy-development, and healthy social-emotional development? It will. Learning where every child is on the natural resilience spectrum helps us protect our individual children in both the short and long term.

And happily, too, by focusing on resilience building as a primary goal of parenting, we gift to the world our children, resilient assets the world needs, a Reacher, Roscoe, Finlay, neighbor, spouse, partner, parent, teacher, leader, friend who will lead others in the future with strength and purpose.

For more on the complex journey of resilience-building, stay tuned for the third and fourth essays, and please consider coming to our Virtual Summer Training Institute in late June. Resilience-building will be a topic in nearly all of the keynotes and workshops. To learn more and to register, click: https://gurianinstitute.com/events/gurian-summer-institute-2022/.