Is it time for the American Psychological Association to look at the neuroscience of teaching and learning?

Gurian Institute Data Shows Boys and Girls Learn Differently Model Works

Image by Taylor Flowe on Substack

Image by Taylor Flowe on Substack

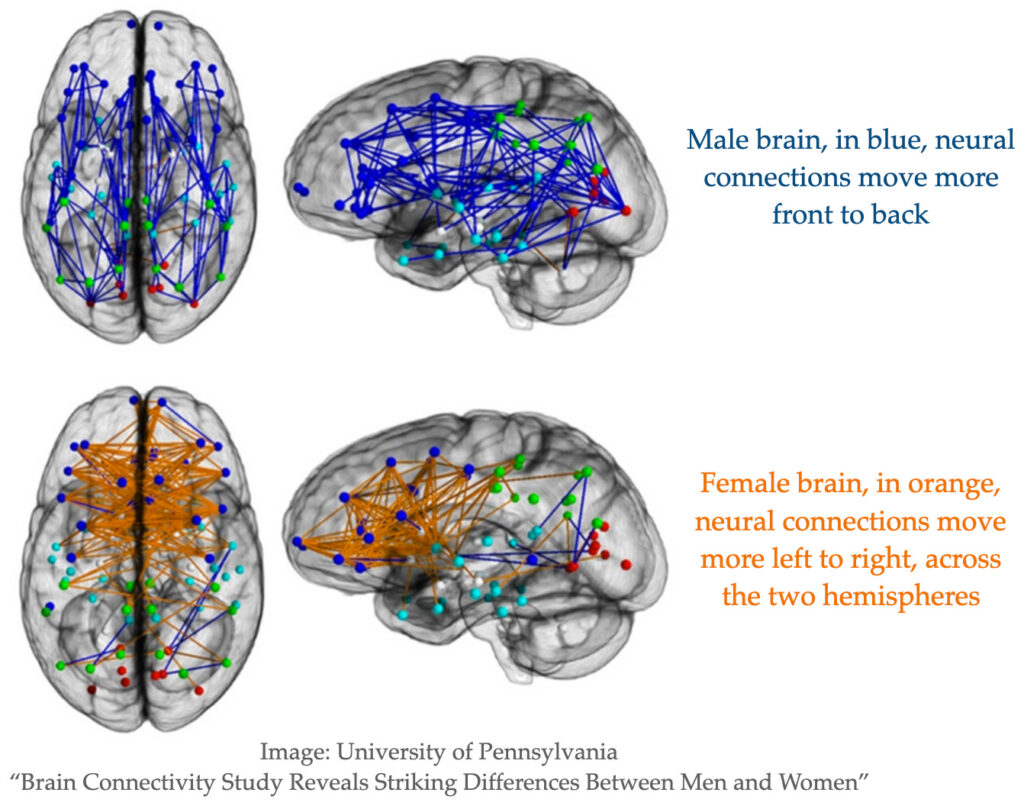

For over twenty-five years, the Gurian Institute has been working in schools across the country to help boys and girls learn differently so they can actually learn better. And for the most part, Gurian relies on a brain-based model that begins with a seemingly elementary neuroscience premise: “brain differences between the sexes call for different teaching strategies.”

It is that premise that has produced dozens of books, including New York Times best sellers, and unquestionable success in coeducational and single-sex schools and districts across the country that make the Gurian Success Model unique. The Gurian Institute is a combination of research, education, active engagement in the classroom, and data driven results on various measures.

And one of its largest educational outreaches takes place in June, when the Gurian Institute will hold its 25th Annual Summer Training Institute virtually on June 24 – 25, with videos available of the sessions through July 10.

Result Driven Outcomes Based on a Neuroscience Model

At the heart of the neuroscience model is decades of work in classrooms and pedagogical approaches that recognize biological differences happening in male and female brains, something discussed in a three part series at In His Words in December of 2022, Part 3. Intersections of America: How Children Learn: C.A.R.E. and the Brain.

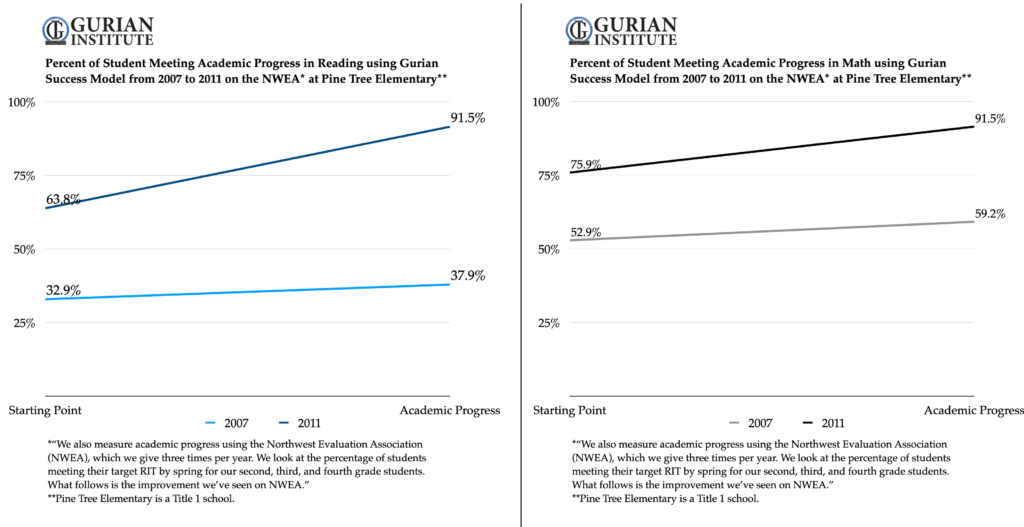

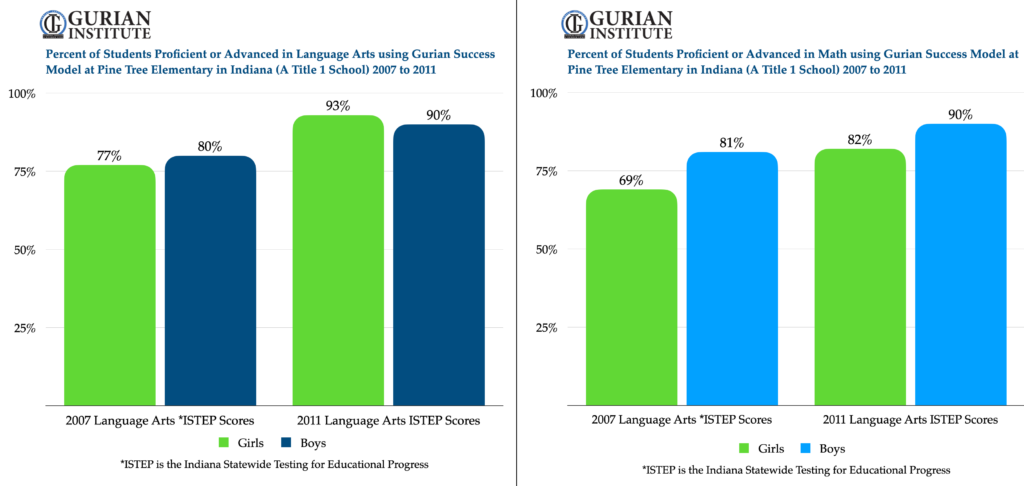

Results at Pine Tree Elementary in Avon, Indiana (a Title 1 school) reveal the brain-based approach to learning in two different testing measures in Language Arts/Reading and Math. Student outcomes from two unrelated testing agencies showed impressive gains in reading and math. The graphs below show student results on the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) assessment of progress as well as the Indiana State Testing for Educational Progress (ISTEP).

NWEA is used in “9,500 schools, districts, and education agencies in 145 countries.” NWEA focuses on student progress throughout the year to ensure students are meeting targeted goals, a process more schools should consider adopting as it measures student progress in real time before students disengage from learning and miss important targets. This type of process allows educators to monitor academic progress and challenges before the end of the school year.

Indiana State testing data also showed impressive gains in Language Arts and Math for boys and girls from 2007 to 2011.

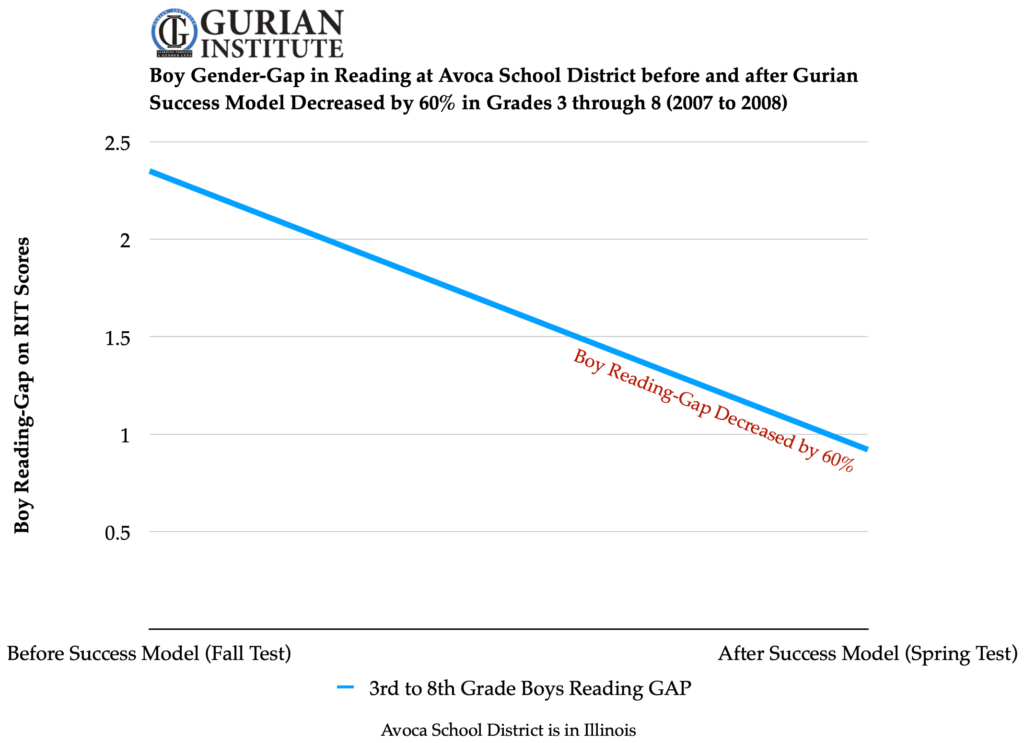

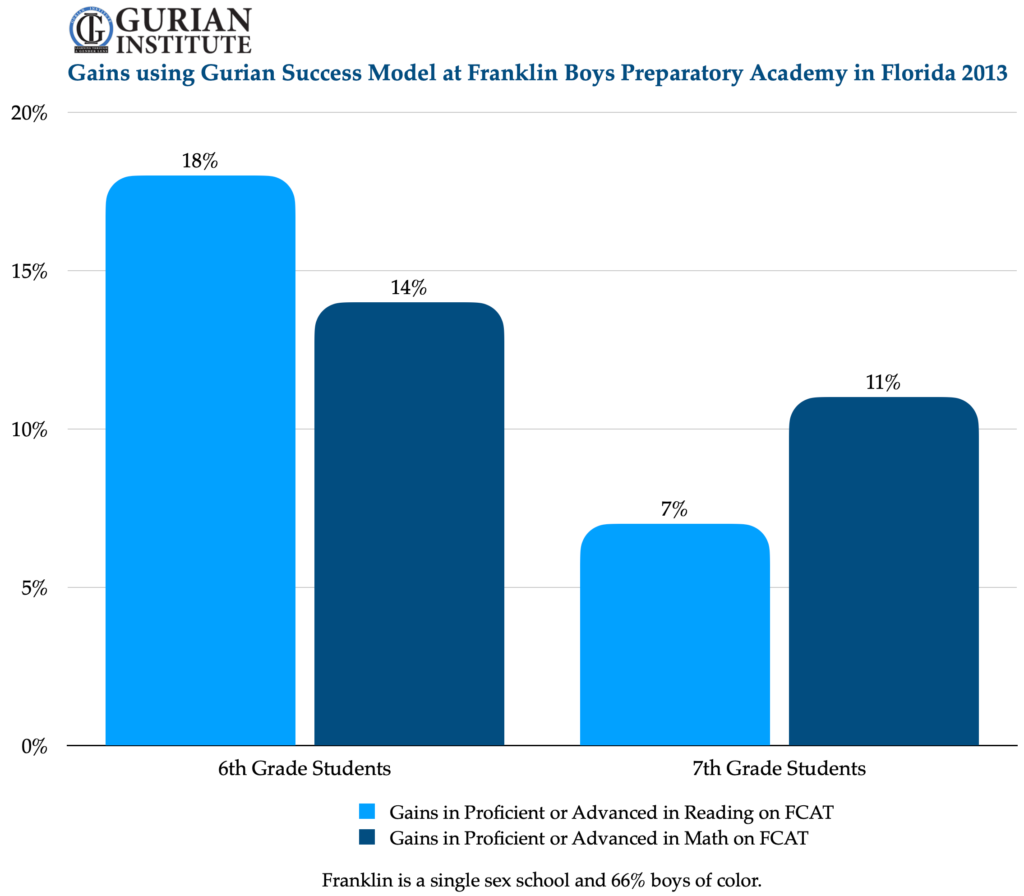

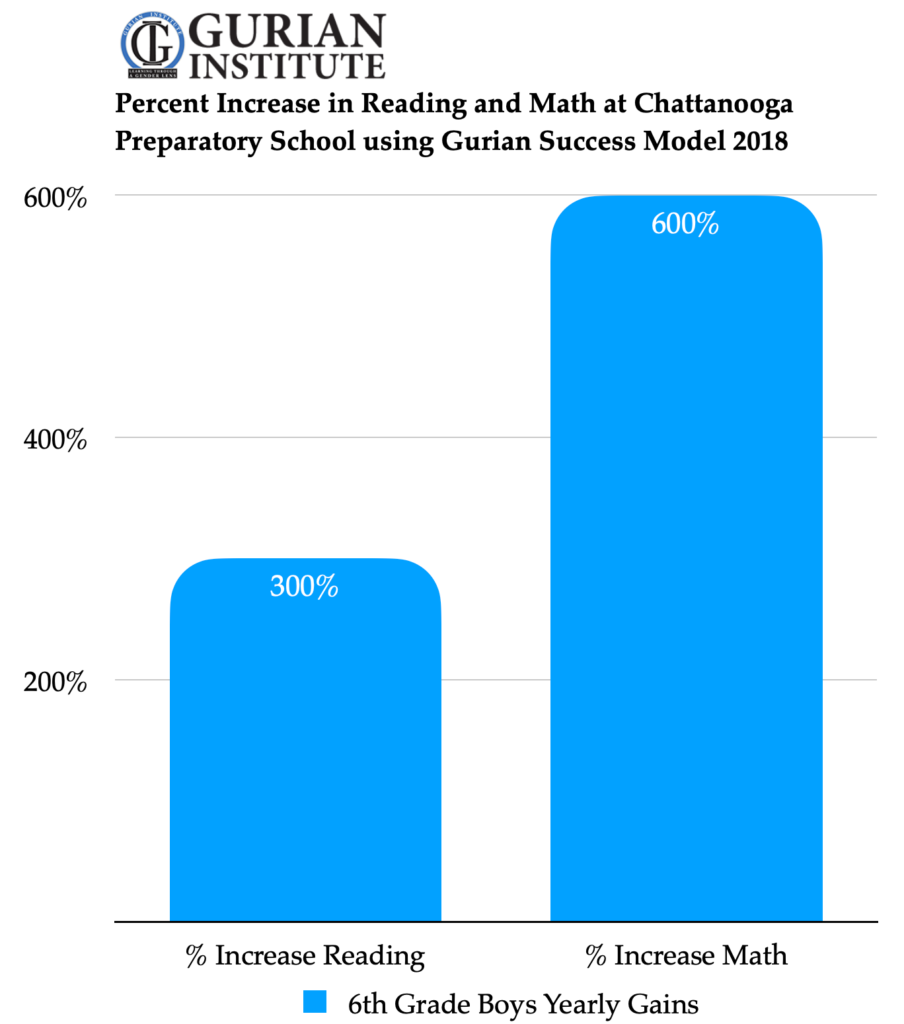

Positive results were also found in Avoca School District, where the boy reading-gap decreased by 60% on the RIT scale after using a boys and girls learn differently approach. Franklin Boys Preparatory in Florida, Chattanooga Preparatory in Tennessee, and a host of other schools and results can be found on the Gurian Success page and the Test Data and Statistics page.

The American Psychological Association recognizes “boys of all ages are doing worse than girls”

Groups like the American Psychological Association have become increasingly concerned about the outcomes of boys. In a recent article addressing the real challenges boys face in school, the APA announced it has formed a task force “spotlighting the specific issues and recommending evidence-based ways to enact swift change.”

While the APA is looking at the research behind things like single-sex school outcomes, redshirting (starting boys later in school), and other approaches, the article did not discuss the neuroscience of learning often employed by the Gurian Institute, the notion that boys and girls learn differently. It will be interesting to see if the APA task force will look at the neuroscience-based models of classroom teaching since it is “evaluating the efficacy” of single-sex school outcomes. Looking at the efficacy of single-sex schools is more complicated than simply looking at schools that place girls and boys into different classrooms or different schools. It’s about getting the brains actively engaged in learning. A deeper dive into the pedagogical approach at single-sex schools is an especially important component in the evaluation process. According to Michael Gurian,

In single sex classrooms or schools, when a non-trained teacher is confronted with 30 boys or 30 girls, it can be overwhelming and confusing. Classroom management becomes an issue, homework doesn’t get done, discipline referrals become a problem, and learning levels can decline. Once the school wide culture is trained in how boys and girls learn differently, a lot of these negatives go away. If the school doesn’t get training in this, it can fail.

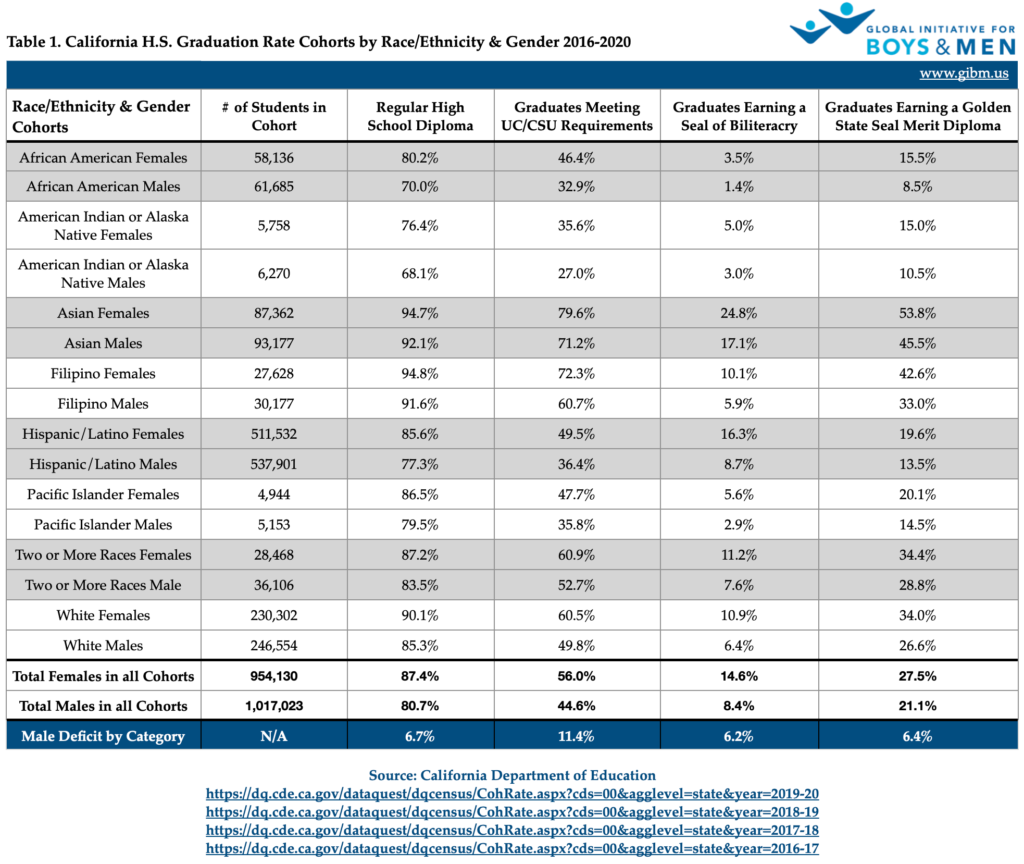

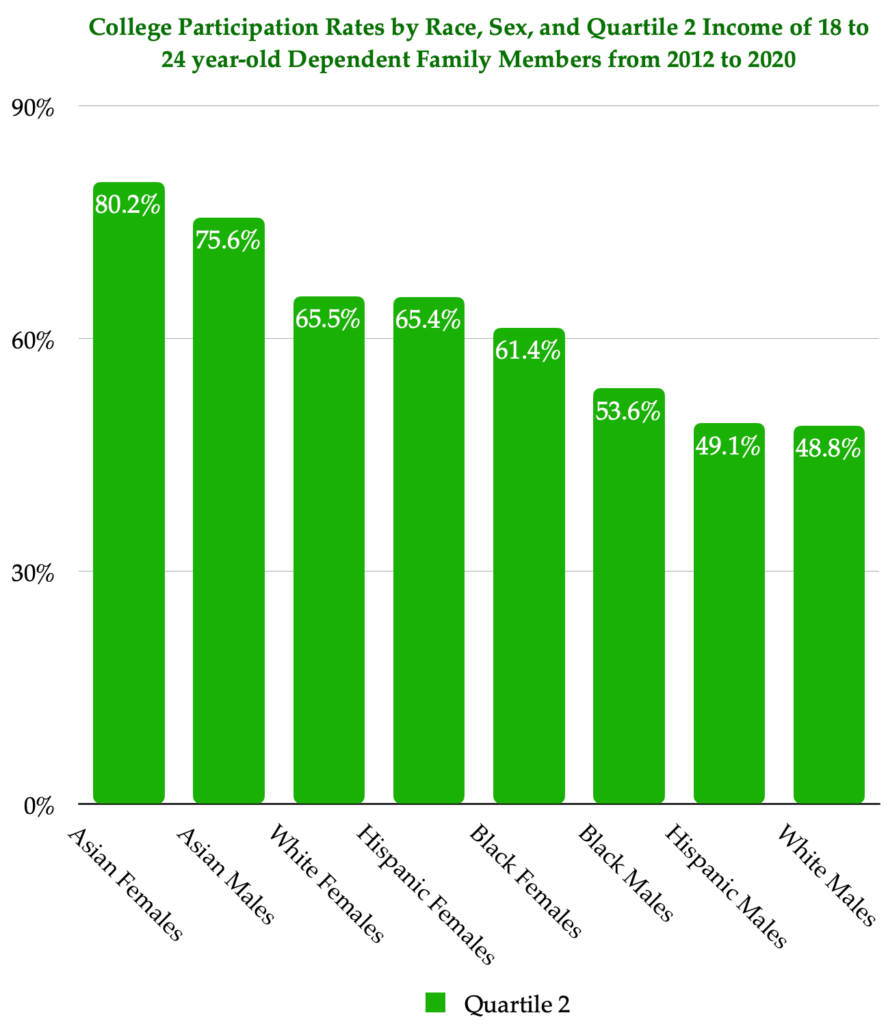

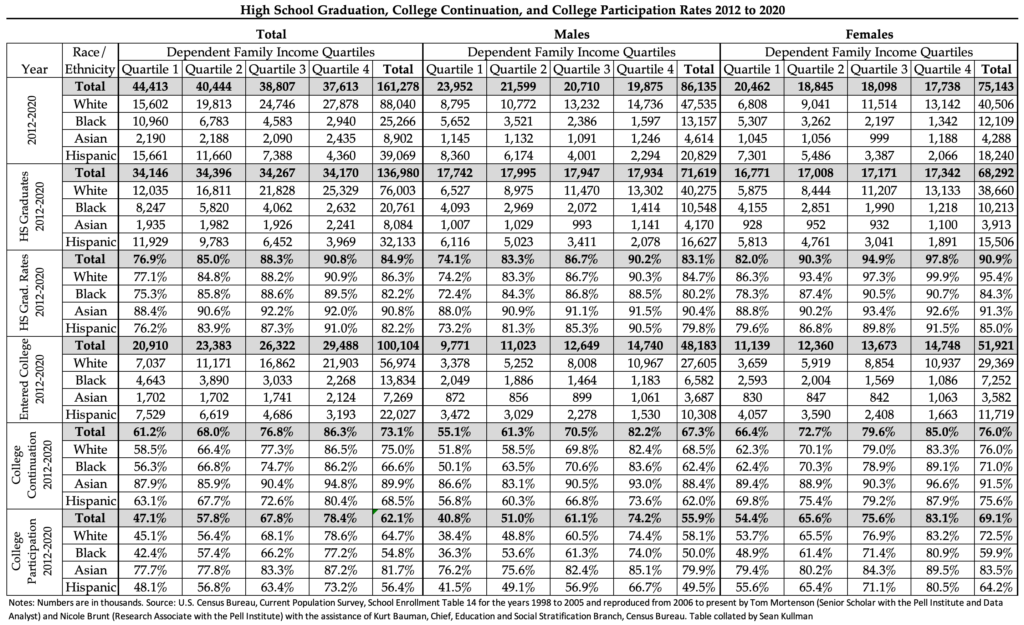

Even as race-based outcomes continue to draw concern and should, it’s important not to lose sight of other sex-based outcomes when data is not disaggregated by both race and sex. Although black boys struggle more in school, boys overall struggle more. The common factor may have much more to do with sex and other social factors than race. It’s something that needs much more attention, as schools are not prone to disaggregate data by race, sex, and other factors.

A review by Global Initiative for Boys and Men of two-million college readiness scores from 2016-2020 in California showed that the percent of White males meeting UC/CSU college requirements (49.8%) were similar to those of Hispanic and Black females (49.5%, and 46.4%) respectively. In a list of 16 student cohorts disaggregated by both race and sex, White males were 8th on the list when it came to meeting UC/CSU college requirements and were statistically similar to 4 other cohorts on the list, ranging from 7th (52.7%) to 11th (46.4%).

There is, unfortunately, a social narrative that is overlooking the outcomes of white boys, particularly those in lower economic quartiles and this is a missed opportunity to identify learning models that can help all boys and identify other factors contributing to poorer educational outcomes.

Webster County High School in West Virginia is 97% white. Male proficiency in reading is 25%. Webster County High School is one of many such schools across the country that face similar challenges. It is likely other factors, such as fatherlessness, socio-economic conditions, preparedness of teachers and schools, and schools struggling to administer education to a male cohort in general are root causes of these problems that reach across all racial groups.

According to one study, “boys of color experience minor and major disciplinary actions at higher rates (2 to 5x) than White male classmates.” Not mentioned is a significant factor when it comes to the outcomes of black boys. 70% of black births are out-of-wedlock. (In 2021, 62% of Native American children in New Mexico lived in a single parent home.) Although American Indian and Black males proportionally struggle more, other factors impacting outcomes may play a greater role.

Challenges facing boys are systemic in nature and cut across all socio-economic groups. There are other factors schools need to become increasingly aware of as they attempt to improve outcomes for boys and girls by creating atmospheres that ultimately improve academic skills. Although statistics regarding single parent homes are not specifically mentioned in the APA article, there is a recognition that hiring more male teachers, pairing boys with male role models, and college male success centers are part of the solution. In other words, there is a recognition that boys need men in their lives. The outcomes for black boys and other boys cannot simply be quantified by race. It’s imperative we look at skill gaps first and foremost and how best to improve measurable and quantifiable outcomes in subjects like reading, writing, and math through pedagogical approaches and a recognition of familial and social factors that present obstacles to learning.

Although American Indian and Black males proportionally struggle more, other factors impacting outcomes may play a greater role. Challenges facing boys are systemic in nature and cut across all socio-economic groups.

After an analysis of dependents 18-24 years-of-age in four economic quartiles from 2012-2020 (approximately 161 million households) was reviewed, it was clear Black, Hispanic, and White males were behind in all economic quartiles when it came to college participation rates. Additionally, these males were similar in their participation rates across all quartiles except for Hispanic males in the 4th (highest) economic quartile (See appendix of tables).

To see all quartiles, go to the article American Education in Black and White.

The Male Gender-Gap in colleges today is part of a larger systemic K-12 program trying to impart skills to young learners. In addition to understanding outside factors that impact learning, a focus on pedagogical methods that engage learners in the classroom and show measurable and verifiable outcomes is especially needed. Understanding neuroscience as it pertains to the classroom is another important component. Encouraging schools of education to include coursework in boys and girls learn differently and getting schools to employ these models in school is something the APA and schools across the country should look at much more closely.

Appendix of Tables

originaly published here https://gibm.substack.com/p/is-it-time-for-the-american-psychological