Sean Kullman, Director of the Global Initiative for Boys and Men, has published a powerful series of articles that pertain to child development and education, specifically what is happening with our boys. This week we are featuring Part III of his series, a section of which looks at the work of the Gurian Institute.

We hope you’ll join us at our Summer Institute this June to learn more about this kind of work. Now here is Sean’s article.

In Part 1 of the “Intersections of America: Why institutions, journalists, and educators need to cross the intersections of race and sex,” the discussion focused on the ways various institutions, policies, and public rhetoric prioritize the outcomes of certain groups while systematically dismissing others. Education, healthcare, and government agencies are often uninformed regarding the outcomes of boys and men because there is so much less in the way of government infrastructure and institutional commitment.

In Part 2, Global Initiative for Boys and Men identified four important institutional reforms to help support, facilitate, and direct resources toward programs aimed at improving the lives of boys and men in a number of areas.

In Part 3, we explore practices to helping boys thrive in school. Successful educational approaches are overlooked at the highest levels of the educational system and in policy actions while certain smaller grassroots efforts are finding success. Thousands of schools across the country are navigating educational landscapes with limited awareness of the ways brain function impacts learning.

In order for students to find success when it comes to mastering skills, it’s important to understand the cognitive awareness and cognitive readiness of students when it comes to things like decision making, behavior, and the best approaches to stimulating the brain. Cognitive awareness and cognitive readiness apply to students and teachers, who are attempting to stimulate the brains of students whose networks in connectivity are more front to back (males) or left to right (females). Understanding the brain that tends to function more in each separate hemisphere and the brain that functions across both hemispheres to a greater degree partly explains the reason boys and girls learn differently. This, of course, is not an absolute, but certainly true in the majority of boys and girls.

Other factors impacting the brain include the ways neural transmitters and hormones (estrogen and testosterone) affect the brain during learning and development. This partly explains the more pronounced brain differences in adolescents aged 14-17, when testosterone in males is accelerated during puberty. Imaging technologies are providing unique looks into the brain and this provides a golden opportunity for educators, coaches, parents, and those working with boys and girls to learn more.

The authors of a University of Pennsylvania study “observed only a few gender differences in the connectivity in children younger than 13 years, but the differences were more pronounced in adolescents aged 14 to 17 years and young adults older than 17.” The observed, gender differences, although fewer in those younger than 13, does not mean boys and girls learn the same. There is a cognitive timetable and other factors to consider.

Generally speaking, the cognitive timetable for development in boys and girls differs. These are not absolutes but true in the aggregate of males and females.

Implementing C.A.R.E. (Cognitive Awareness-and-Readiness in Education)

C.A.R.E is an essential component to educating our children, a reform that includes schools of education and classrooms across the country to engage in educational approaches that look at a brain-based model of learning, not as the only way to teach but as an essential way to teach. Thousands of teachers go through schools of education but may never learn about the brain differences in males and females that impact learning and the lesson plans that help facilitate that learning.

Parents of sons and daughters often comment that school is built for girls and not for boys. And their observations have merit. Male Gender-Gaps in suspensions and reading happen across all racial lines and clearly indicate that schools are having a harder time educating boys. Girls, generally, sit more quietly and seem to operate with executive function. Boys, generally, drift off and start looking for action. These are not simply attention-deficit-disorders that need drug interventions. These are pedagogical disorders that need an infusion of more contemporary approaches to learning.

Some educators, researchers, and practitioners have been calling on a brain-based approach to learning, the recognition that practices in the classroom need to mirror the biological differences in the brains of boys and girls. Others see cognitive development as a scale, where boys develop later than girls and educators need to account for that difference.

Regardless of one’s position on these approaches as collective or unique solutions, there is no denying the ever widening Male Gender-Gap in K-5, middle school, high school, and college education. These trends cut across all racial lines and are found in state test scores, national test scores, suspensions, and college readiness, participation, and completion rates. (These outcomes, of course, spill over into other concerns; homelessness and suicide and overdose deaths. All of which are overwhelmingly male.)

Schools and Brains

There have been mixed reviews regarding single-sex schools, with some studies showing no difference in performance and other studies showing differences in performance that benefit boys and girls. There is a logical reason some single-sex schools struggle to get positive results and others find success. Simply splitting girls and boys into separate classes is not enough.

Michael Gurian, Founder of the Gurian Institute and author of Boys and Girls Learn Differently, has spent three decades helping teachers and schools implement brain-based education to improve the outcomes of boys, girls, and students on the gender spectrum. Gurian has produced some of the most important work in the field. I asked Gurian about the challenges of single sex schooling and implementing brain-based learning approaches in schools generally and why some schools are more successful than others.

“When schools or classrooms go awry–or just don’t produce good outcomes–it’s almost always because of lack of training among staff in how to teach and mentor boys specifically and how to teach and mentor girls specifically. When the teachers and staff do get comprehensive training in male/female brain and learning difference, classroom culture succeeds and so do the kids.

But especially in single sex classrooms or schools, when a non-trained teacher is confronted with 30 boys or 30 girls, it can be overwhelming and confusing. Classroom management becomes an issue, homework doesn’t get done, discipline referrals become a problem, and learning levels can decline. Once the school wide culture is trained in how boys and girls learn differently, a lot of these negatives go away. If the school doesn’t get training in this, it can fail.

“Thus, if I had to pick a single key to making classrooms work for all children, whether coed and single sex, it would be teacher training in how boys and girls learn and grow differently. Our Gurian Institute data (housed on www.gurianinstitute.com/success) records this key point statistically. Teachers are smart already: once they are trained in natural male/female learning and behavior difference, they teach well to all children, including the difficult boys, and all the kids can succeed.”

It’s important to realize that entire schools do not need to be single-sex for single-sex classes to take place and that co-ed classrooms can use brain-based strategies to help boys and girls succeed. However, single-sex schools have found success in both the public and private sectors for many children. Closing our minds to a variety of avenues for children is antithetical to the goal of helping children experience positive, measurable outcomes. But not engaging more in brain-based learning, behavior differences, and cognitive development overlooks crucial steps.

Richard Reeves recent book Of Boys and Men has called for red shirting, starting boys later in school, as a way to address the cognitive differences in male and female brain development in the early years that contribute to poorer outcomes in the later years. Reeves “proposes that boys be red shirted by default,” noting, boys are more likely to be red shirted than girls, especially by parents who are teachers. Children who are younger for their school year are also more likely to be held back a year. When these factors are combined, the rate gets quite high. Among summer-born boys with BA-educated parents (the kind of folks who read [Malcolm Gladwell’s] Outliers,) the red shirt rate is 20%…. And far from being those at the most educational disadvantage, children who are red shirted have slightly above average literacy and math scores when the decision is made. In other words, the boys who benefit the least are the ones most likely to be red shirted. A raft of studies of red shirted boys have shown dramatic reductions in hyperactivity and inattention through the elementary school years, higher levels of life satisfaction, lower chances of being held back a grade later, and higher test scores. (See chapter 10 of Reeves Of Boys and Men.)

Reeves has noted that “delaying school entry could put pressure on parents to provide childcare.” This challenge could be resolved with pre-k opportunities, as Reeves has mentioned. At the least, parents could be given the option to consider the red-shirting approach.

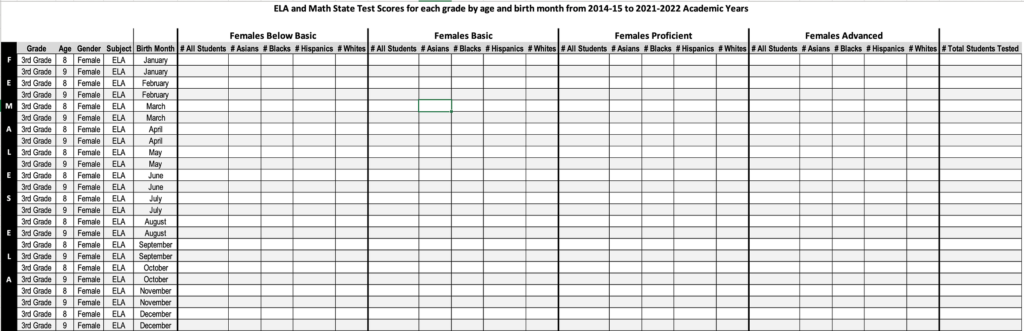

One thing that would help is a data release of student outcomes in grade 3 thru 12 that show the aggregate scores of male and female cohorts by grade, birth month, and age. The table below is simply one example of one grade level that could be reproduced for many grade levels. (For a full copy of the GIBM K-12 performance of students by age, month, and sex spreadsheet, click here.)

The data in the table above is already available if departments of education, school districts, and individual schools are willing to disaggregate data fully; otherwise, policy makers and teachers are operating from incomplete information and potential solutions. GIBM noticed this problem in California, where districts often conflate race and sex instead of disaggregating by race and sex. They now need to go one step more and include age. Although one district in California used suspension data as part of its impetus to hire a diversity, equity, and inclusion consultant at $250,000 to address a perceived implicit bias, the district failed to acknowledge the Male Gender-Gap in reading and the more accurate reflection of suspension data: Black, White, and Hispanic males had suspension rates that were significantly higher than any other group of females. Suspensions were more of a sex-based outcome than a race-based outcome. And it was far more likely the school was struggling with Male-Gender-Gaps, and that many students who were finding success were doing so through parents who augmented their children’s learning outside of school. The test scores in affluent school districts may be partly higher because parents use their resources to help their struggling sons and daughters. After looking at nearly 2-million student outcomes in California, it was clear sex played a larger role in college readiness than race, according to data from the California Department of Education (see table 1 in appendix of tables).

I’ve encouraged a California school district to use the performance of students by age, month, and sex spreadsheet above to determine if there is a variance in the reading scores and math scores of students who are approximately a year apart but are in the same grade. For instance, what are the scores of third grade males/females who are 8 in June vs. those who are 9 in June? (Schools should also separately provide data on students who have been retained.)

The school district has largely missed the opportunity to learn from this type of data. GIBM is looking into next steps to encourage this district and others to produce this data and share it with the public.

The above request is predicated on some engaging findings. Educators and BA educated parents are the ones most likely to delay school enrollment into kindergarten for their children. As Reeves has noted, “teachers are three times as likely to have delayed the school entry for their sons as for their daughters.” What do teachers know that most do not? The National Bureau of Economic Research produced interesting finding on redshirting. “The benefits of having older peers also appear to be weaker for boys and higher-income children, consistent with the existence of larger relative age effects –and the higher incidence of delay – among these groups.” In other words, having older peers (i.e., boys) does not hurt girls and allows for the delay differences between girls and boys to play out in real time developmentally. But this should not serve as a substitute for the very real biological differences happening in the brains of boys and girls. As I said earlier, these approaches are not exclusive of one another and the reason more needs to happen at the institutional level when it comes to openly addressing these approaches.

An Office of Boys and Men in Education and a White House Boys and Men’s Policy Council could help dramatically change the landscape of data retrieval and pedagogical approaches that lead to successful outcomes for boys and girls.

School districts are spending enormous sums of money on programs that result in grading policies that incorporate “grading equity” instead of programs that improve student skills. In at least one California school, intervention specialists are now taking the place of reading specialists. This programmatic decision removes those most vulnerable from those most capable of teaching struggling readers (reading specialists) and replaces them with cheaper intervention specialists, computer software programs, and grading policies that are not improving essential skills. All this happens while grass roots efforts, like educating through a gender lens and individual parents making decisions that best fit their children’s needs, take hold on a smaller scale when something more bold is needed.

Poorer educational outcomes will continue if policies and practices are not questioning the status-quo and instead looking for a new way to go. C.A.R.E is an important step forward and one that needs to find a place in the classroom and in the White House.