An essential component of the article addressed some of the educational outcomes in Livermore Joint Unified School District, and InHisWords was asked to do a deeper dive into the outcomes of boys and girls in Livermore Joint Unified School District (LJU SD) by educators and parents.

We researched the outcomes of over 50,000 student scores on the CAASPP (California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress) for third to eight grade students and eleventh grade students from 2014 to 2023. Research and funding were supported by GIBM (Global Initiative for Boys and Men) and carried out with the help of airr (American Institute for Responsible Research).

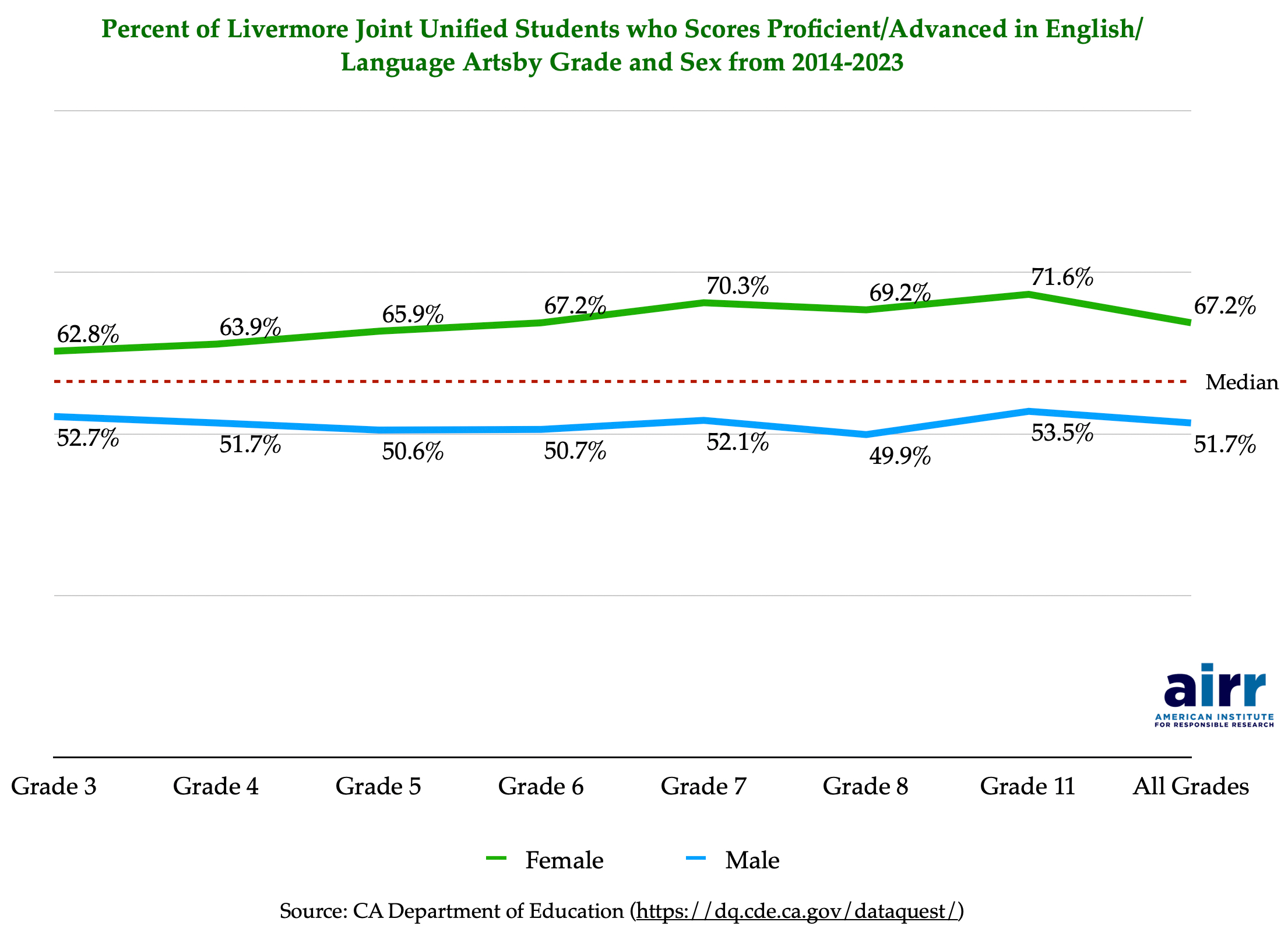

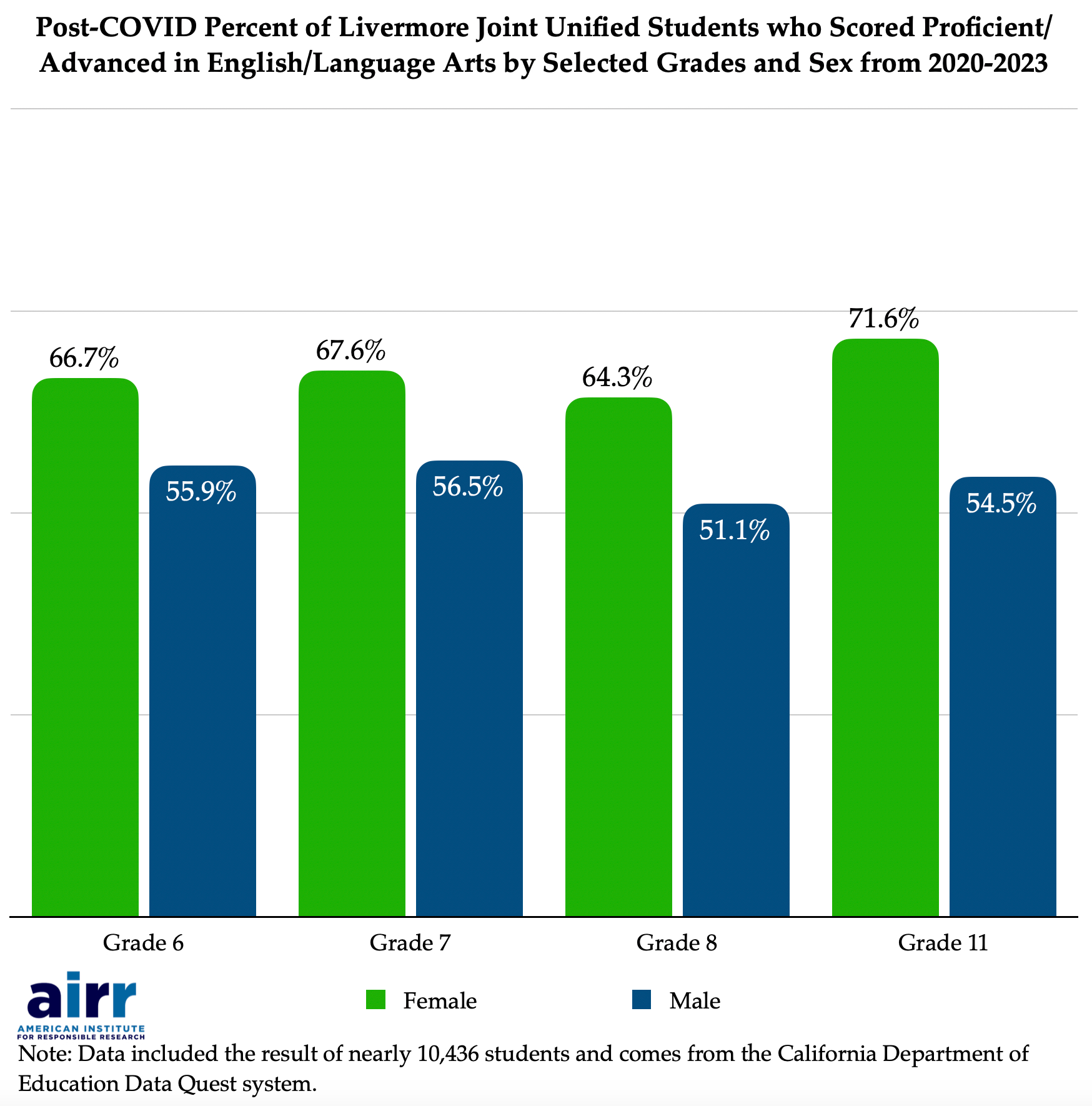

The results show that boys are behind girls at all grade levels in English/Language Arts (ELA) and that the gap tends to widen around middle school. In third grade, boys are 10.1% behind girls in reaching proficient/advanced scores in ELA. In eighth and eleventh grades, boys are 19.3% and 18.1% behind girls respectively.

The results show that boys are behind girls at all grade levels in English/Language Arts (ELA) and that the gap tends to widen around middle school.

After sharing the data with an educator in a nearby district, she offered up the following observations and advice.

When looking at the data, it is sadly not surprising. Our schools have been built on the premise of being able to sit and to listen for extended periods of time. If you did that, you most likely succeeded.

However, we know this is not a conducive environment for our boys. As an educator for over 20 years, both in the classroom and as a reading specialist, I have watched boys having difficulty sitting still and focusing for extended periods of time.

Walk into any lower elementary classroom and you will see the boys moving more, needing reminders to sit “properly” and to attend more. At the secondary level, lecture is a common mode of instruction, with lessons often involving reading/writing long passages within a set time frame.

Reading and writing are in their very nature passive. We sit for extended periods of time engaged in an activity that requires focus. So it is not surprising that our boys are performing lower than our girls in this area.

Often, the boys referred for reading intervention at the lower elementary level are boys that also exhibit the boy behaviors that are tied to their biology. Brain science shows that boys’ brains (in the aggregate) develop at different rates then girls, especially the frontal cortex which is responsible for impulse control and that boys’ brains go into full rest mode more often than girls’ brains.

From an observational point of view, effective strategies implemented in classrooms for the boy brain are breaking lessons down into smaller chunks.

- (1 minute for every year of age up to 15)

- intentionally and strategically placing movement and tactile experiences throughout the period or day

- options to sit or stand (flexible seating) during the lesson and/or independent work.

As educators we must start looking at the data through the lens of brain science and sex/gender, be intentional in the strategies we implement based on the science and study the impact in the ELA data over time.

Follow the Trends

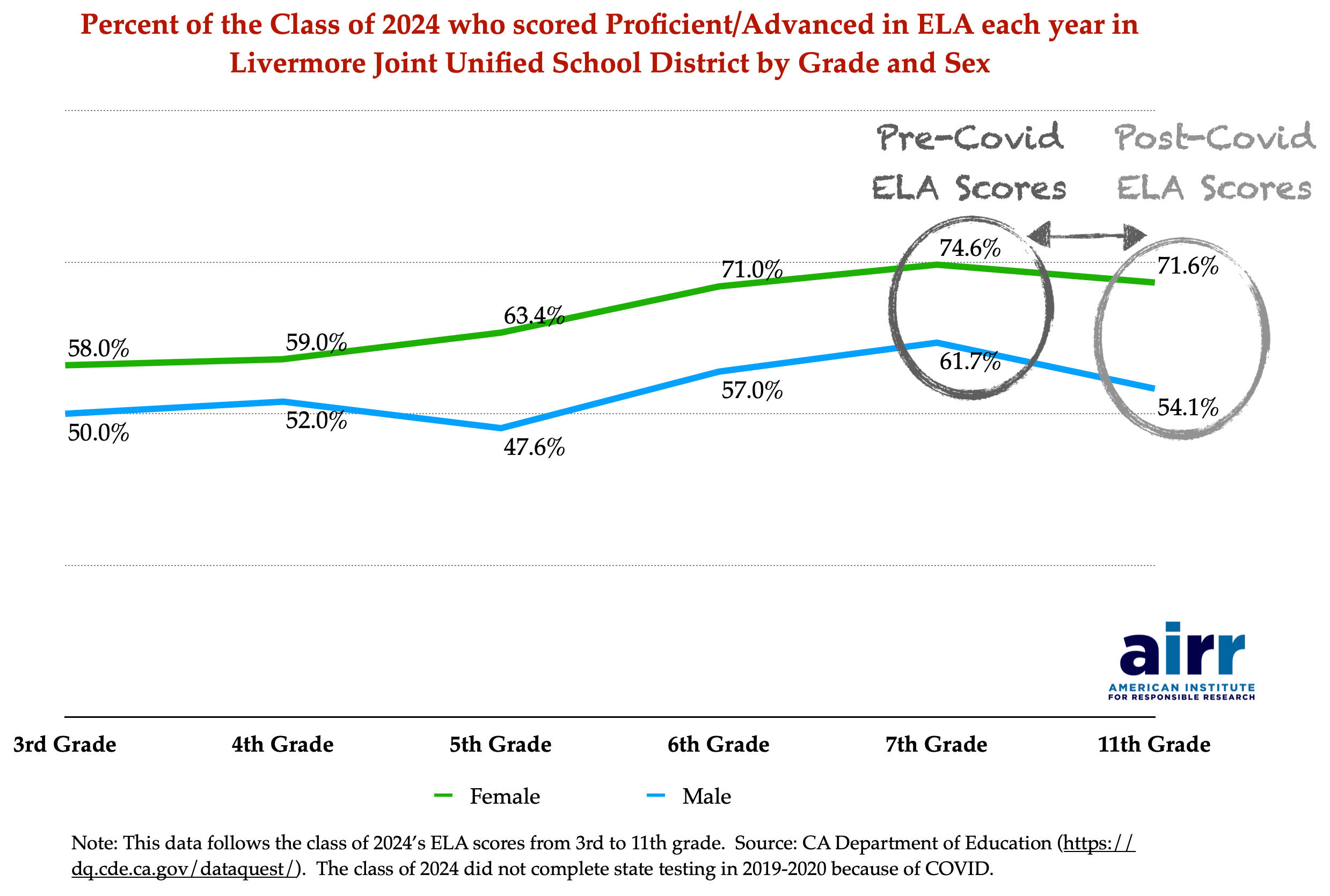

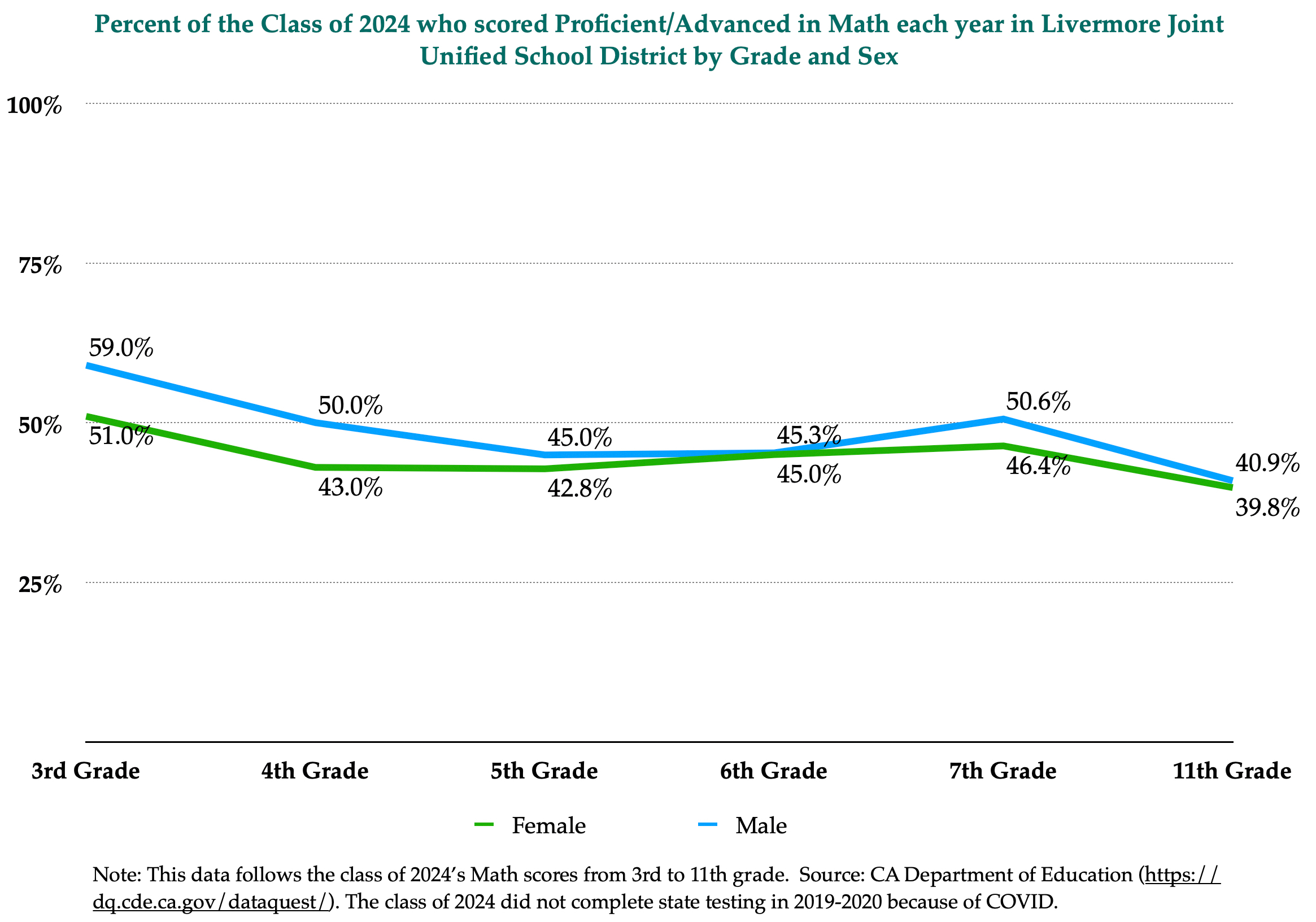

Our data in the graph below looked at the class of 2024, those who will graduate this spring, and followed their academic journey that started in third grade in the 2014-15 academic year. The data did not include eight grade results because students were not tested during COVID year 2019-2020.

While data appears to suggest boys and girls were on an upward trend some time around sixth grade and into seventh grade, boys showed a sharp decline sometime over the next four years that COVID cannot completely explain. Girls scores remained relatively the same even through COVID from sixth to eleventh grade. Boys scores dropped dramatically over the same time period. This systemic trend has been happening for some time in Livermore Joint Unified School District.

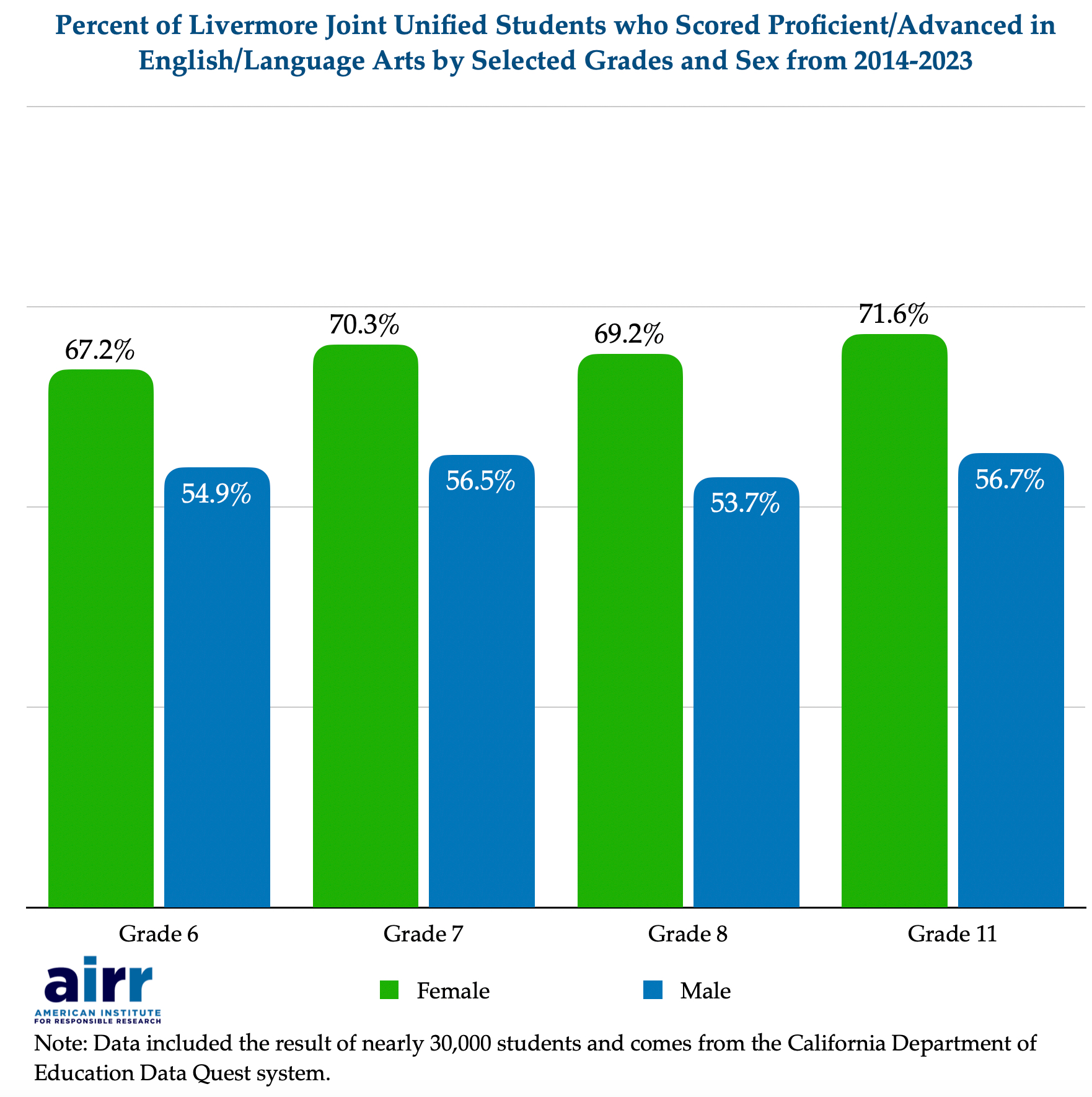

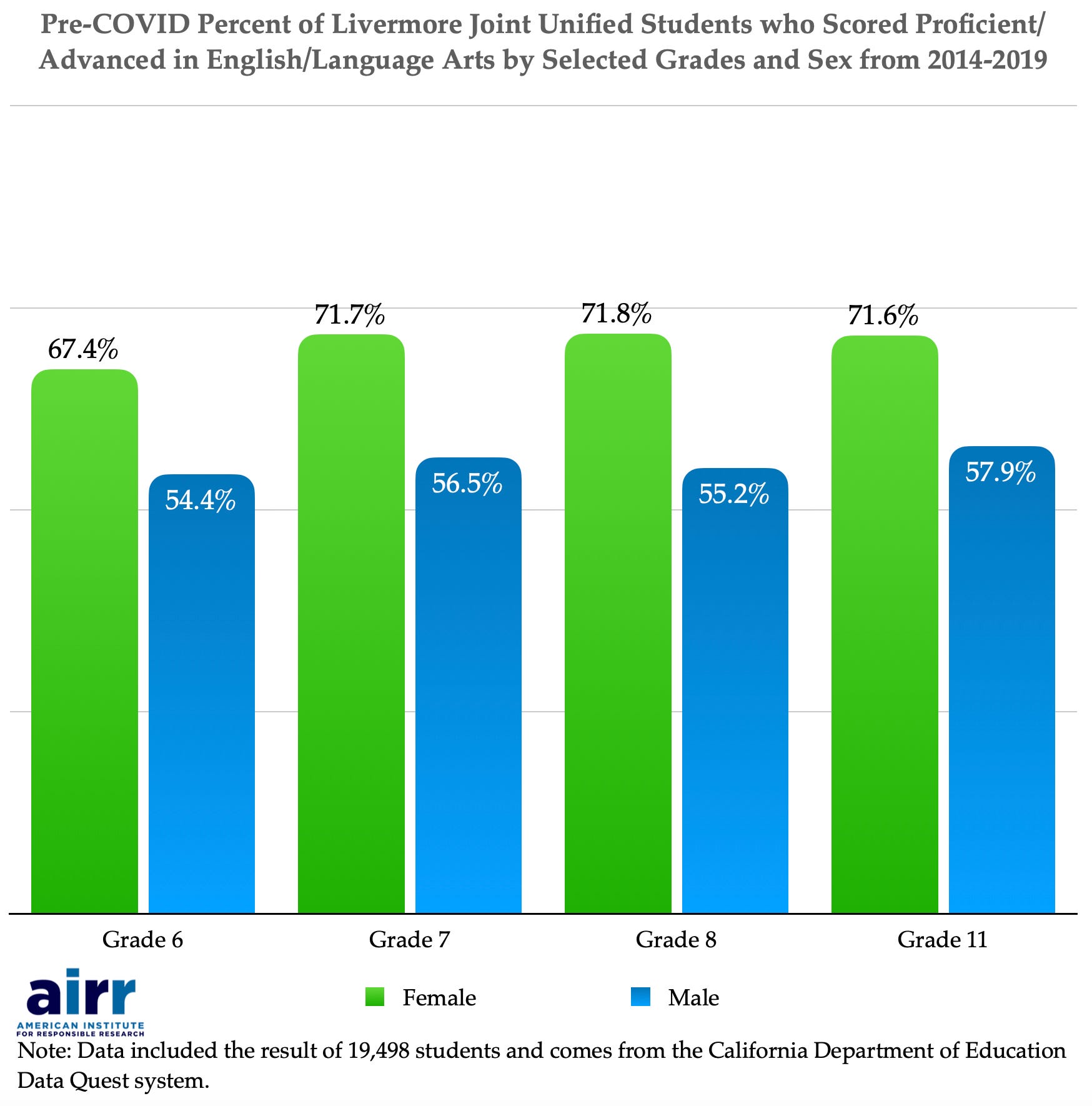

A review of nearly thirty-thousand test scores of sixth, seventh, eighth, and eleventh grade students from 2014 to 2023 showed that boys scores tend to wane during middle school in LJU SD, and this pattern continues into high school. Pre-COVID and post-COVID results reveal the same pattern, as the three graphs below show the combined results from 2014-to-2023, pre-COVID results from 2014-to-2019, and post-COVID results from 2020-to-2023 of students in LJU SD.

It’s not only that boys are far less likely to score proficient/advanced that their female peers, a higher percentage of girls score advanced than the percentage of boys who make it to proficient by eleventh grade. While 39% of eleventh grade girls scored advanced in ELA from 2014 to 2023, only 29% of boys made it to proficient and only 28% scored advanced.

A female student is more likely to score advanced in ELA by eleventh grade than a boy is to score proficient. Additionally, the percentage of girls who score advanced nearly matches the combined percentage of boys who nearly meet and do not meet standard levels (43%).

For every 100 eleventh-grade boys in LJU SD who score advanced in ELA, there are 143 girls.

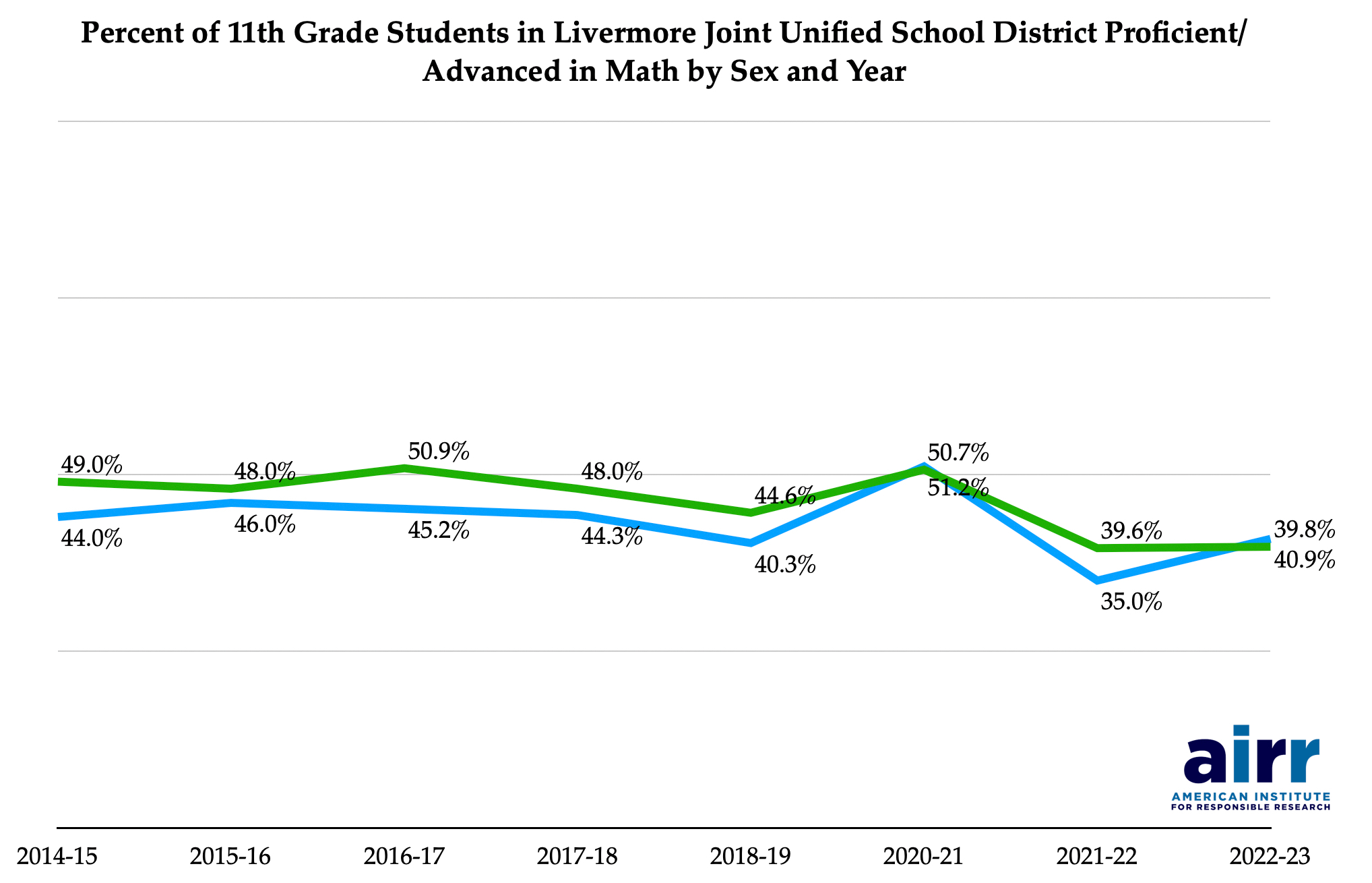

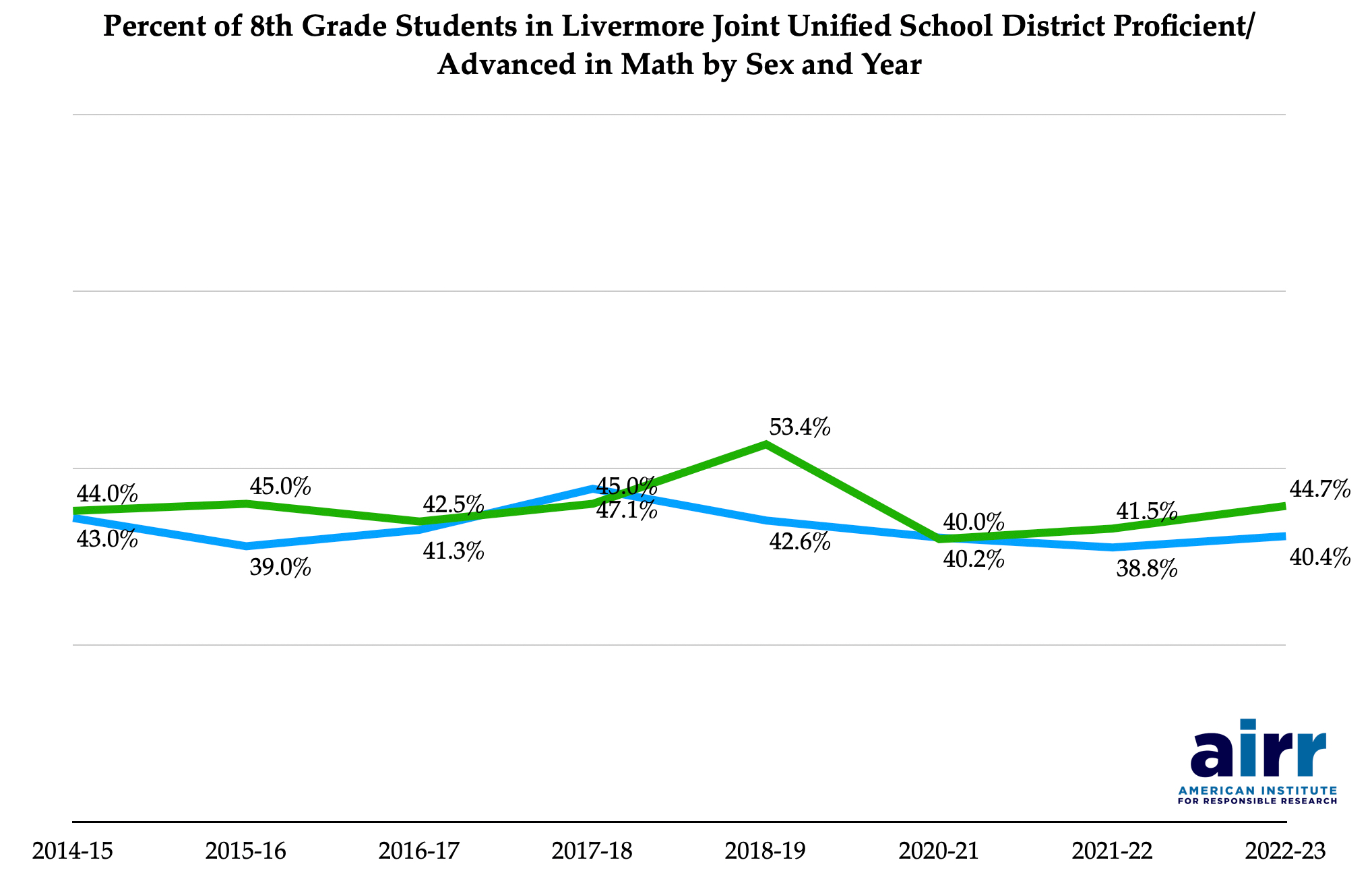

Although much is often made about disparate outcomes in math, this is not the case in LJU SD and many places. From 2014 to 2023, girls (46.4%) slightly outperformed boys (43.1%) in eleventh grade math as well as eight grade math 45.1% to 41.6% respectively. These margins are considerably smaller than the Male Gender-Gap in reading, but the data reveals the general challenge the educational system is having with boys. (And it has not escaped us that there is a downward trend for boys and girls.)

The research also followed the downward trend for the class of 2024 in math that started long before COVID. And LJU SD, like many districts, are struggling to improve learning in math. Boys in the class of 2024 saw their math scores drop 18.1% from third to eleventh grades and girls saw their math scores drop 11.2% from third to eleventh grades.

Avoid Getting Comfortable and Stay Sharp

As one teacher recently shared with me, her school district (not LJU SD) is praising test results because they are higher than the state averages. The district in which she works is one of the wealthiest in the state and with predominately intact families. (Under 10% of couples are divorced.)

School districts may fall into the habit of comparing their scores against a state average even though California has been below national averages in reading and math on the Nation’s Report Card in 2017, 2019, and 2022. This approach is a fool’s errand. School districts need to focus on continually improving outcomes (measured by student proficiencies) in their own districts.

The LJU SD class of 2024, for instance, outperformed the state average in math in the 2022-2023 academic year by some 12% to 13%, but the class of 2024 has shown a marked decline in math proficiency since 2014. School districts need to specifically focus on improving student scores in their own districts and finding successful approaches that may prove fruitful elsewhere.

As districts look to implement policies that improve student outcomes, it’s essential to look at the data and direct resources toward specifically improving skills in math, reading, and writing.

Our findings show, at the very least, that the poorer outcomes of boys in Livermore Joint Unified School District are systemic in nature and that the district is prone to sharper discipline of boys and poorer educational outcomes.

I coincidentally received an email from a friend while writing this article, asking me about biases against boys in the educational system. The biases, I believe, are clear in the outcomes, particularly when they are happening year after year and move from the appearance of causality into something persistent and true. The pedagogical approaches and current school environments at nearly all levels of education are unwelcoming to boys and young men.

Our findings at Livermore Joint Unified School District fall into a long line of school districts that press forward with pedagogical approaches that are leaving boys behind. But this can change if parents and school leaders are willing to look at the data and work with those outside the routine practices of school culture to find solutions that lead to measurable, positive outcomes.