The terms “masculinity” and “toxic masculinity” are used quite a bit in our culture. Last year a wing of the American Psychological Association produced “Guidelines for Practice with Boys and Men,” equating masculinity with mainly negative characteristics, and guiding therapists to try to remove masculinity from male clients as the best way to make men whole. Michael Gurian and others in the boy’s development field were asked to respond to these Guidelines by discussing masculinity in a fairer light and by pushing back at the idea that masculinity comprises the root of our society’s ills.

Over the last year, Michael’s response to the APA Guidelines has been featured in other media, podcasts, and news boards Many of you have asked for the original blog post to be republished. Now, as we approach the new year–a moment that always provides a chance to restart personal life and public interactions–GI is re-publishing this blog post with a new introduction. Healthy maleness and the inherent generosity of masculinity will be a topic of some of our speakers at our Winter Institute Tele-Summit in January (https://gurianinstitute.com/events/gurian-winter-institute-2021/). We hope you’ll join us at this powerful January event for a science-based re-start on educating and raising boys and girls.

The Unfortunate Gender War

Another reason for the republication of this post is a recent Christian Post article in which Michael Gurian and the Gurian Institute are quoted extensively (“Is Gender Equality Shortchanging Boys in Churches, Schools, and Other American Institutions?” https://www.christianpost.com/news/is-gender-equality-shortchanging-boys-in-churches.html.) After being interviewed for the article and then reading the CP article once it was published, Michael said, “I glean from the article and headline that the Post’s reporters and editors are trying to isolate women’s rights movements as a primary cause of boys’ distress today, but I do not pit girls/women’s rights against boys/men’s rights.”

Gurian further notes, “There is a destructive gender war in our culture. Both sides create it and it is tearing us apart. Some people on the Left, likely because of protectiveness for girls and women and their own ideological framing, attack boys/men/masculinity as inherently and systemically dangerous and defective, when they are not; some people on the Right, likely because of protectiveness of boys and men and their own ideological framing, blame the women’s rights movement. By taking this science-based position, I avoid the gender war and focus on elements of distress in the intersection of nature, nurture, and culture.

“I am not naive. I know there are extreme feminists in academe, government, and the media who are androphobic (fear boys and men) and are or appear misandrist (hate men); I also know there are radical factions on the other side of the aisle who are misophobic (fear women) and are or appear misogynistic. But I hope in the new year we will have become so nationally distressed by the dangerous polarization in our culture that we will come together to heal divisions between the sexes. I hope we can do this on behalf of all of our children.”

Masculinity is Not Our Enemy, by Michael Gurian

Something has happened to our academic culture–the culture that teaches educators how to teach, therapists how to counsel, and parents how to parent–and it is both very satisfying and somewhat frightening. Satisfying is that our academic culture is waking up to the fact that boys and men in America need our love and support. Child advocates like myself who are parents of daughters have been saying for years, “We can’t do much more for our daughters if we don’t help their future husbands–our nation’s sons–too.” Many people like you have been asking representatives of national organizations such as the National Education Association, American Psychological Association, and American Medical Association to see what is going on with boys and men.

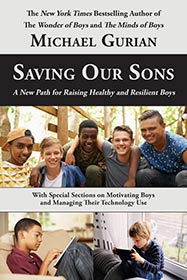

As I pointed out in Saving Our Sons (2017), despite that there are many powerful men at the top of society, there is also no American demographic group in which males in that group are doing better than females in the aggregate. While subsections of females are doing worse than males, there are equal or more subsections of males doing worse than females. Even the World Health Organization made this point in 2015. White females, for instance, have better health than white males and more access to health resources; they have better aggregate grades, test scores, college graduation rates, post-secondary education; they are safer at home and in school than white males…the list is very long, and the same holds true for comparisons of African American, Native American, Latino American, and Asian American males and females. Girls and women don’t have it easy, but neither do American boys have more privilege today than the equivalent girls do, in the aggregate.

When the American Psychological Association put out its Guidelines for Practice with Boys and Men in 2019, I was delighted to see its clarity in pointing out male privation–from high suicide rates to depression, anxiety, addiction, and violence. These are diseases that need treatment, and the APA acknowledged it. But from the first sentences of the Guidelines, the APA did what so many other organizations do: fall back on the soft science of “masculinity is the cause of men’s problems” and “removing masculinity is the solution.” In 2019, I was asked to publicly respond to the APA report, and many of you have asked me to do so, as well. Here is that analysis. My basic point is this: even by the APA’s definition, “masculinity,” which they suggest therapists help us remove from males, is actually a good thing.

Masculinity is characterized, according to the APA, by strength, stoicism, aggression, and power. Like our academic institutions in general today, the APA presents these aspects of masculinity as our nation’s largest male problem. In reality, however, if boys are to survive and thrive in a complex world, they must work to be strong (resilient, empowered, able to perform, and at appropriate times, stoic in the face of enemies and hardship), aggressive (assertive, motivated, and able to battle against bullies, as well as help us fight our wars both abroad and at home), powerful (successful in work, in life, in leadership, and, when needed, in follower-ship to leaders who are morally sound). These qualities are intertwined with tenderness, kindness, compassion, spiritual vitality, empathy, fortitude, character, and fatherhood. We are able to have compassion because we are strong; we are able to live from a position of kindness because we have the power to do so.

As profiles of school shooters have shown us, the most dangerous male is not one who is strong, aggressive, and successful; the most dangerous male is one who is depressed, unable to partner or raise children successfully, unable to earn a living, unable to care for his children. The most dangerous man is not one with power but one who feels powerless. Our culture has focused its media on the million or so males who have a lot of power at the top but, for the most part, forgotten the millions who don’t; these millions live in inner cities and rural farms, gentrified suburbs and city lofts, corner bars and cardboard boxes, gang crash pads and parents’ basements. They are in constant fight or flight mode in a culture that has abandoned them, and every decade we see their withdrawal from and violence against society, and themselves, increase.

In The Wonder of Boys (1996), I argued that masculinity is, at its heart, a “husbanding” vision of strength, purpose, honor, power, and compassion that culminates in the art of building a strong enough male self to be able to give that self to others in love and marriage, in parenting and mentoring, in work and life. Few people were more masculine than Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall–you name it, the men who help us most are each in their own way quite masculine. If we are going to solve issues faced by everyone today–boys, girls, women, men, and everyone on the gender spectrum–we must challenge academic culture to go deeper into who boys are, and what most people in America see very clearly: boys need more masculinity, not less; more fathering, not less; more healthy manhood, not less.

And we must respond when people exploit narrow definitions of masculinity for their own ends. Gillette did this last year in their now famous 2 minute add (check on You Tube for “The Best a Man Can Get”). The ad presented men and masculinity in a basically negative light, and presented normal masculine rough housing as part of toxic masculinity when, in fact, rough housing is a crucial tool in brain development. Interestingly, when Dove and similar companies have created commercials that approach girls’ and women’s lives from a clearly political lens, they have done so by seeking to find the beauty in girls and women, rather than leading with and ending with basically negative portrayals of girls and women. In taking the opposite course, Gillette asked men to be accountable for bad behavior: that part of the ad is admirable, and useful; but, like the APA, Gillette does not understand how important masculine development is to human development and survival. They especially do not understand that above all else, males who seek to be masculine will not countenance violence against women or children. Masculinity is a protective force against violence, not an invitation to commit violence.

Masculinity and “masculine norms” can handle academic and social dialogue. As social forces, they can handle very useful calls for expansion beyond some stereotype of self. But masculinity is fragile, too, as millions of failing males prove. It is too fragile to be accused by our nation’s smartest people of crimes it has not committed. And our sons are too fragile to survive and thrive if those who ostensibly care for them–from academics to businesses to schools to communities–suggest our sons’ biggest crime is their very existence. As McGill University researcher and co-author of Replacing Misandry Paul Nathanson has pointed out: This will lead to self-hatred in boys and men, which is very dangerous, indeed.

Bad men do bad things and some men never grow beyond a small self. To pretend masculinity has caused these social and personal conditions is to distract ourselves from huge areas of real pain all around us. Let’s stop treating masculinity as our enemy: let’s start helping boys to grow into the good men their own personal character and drive want them to be.

Further Response to American Psychological Association Guidelines on Practice with Boys and Men, edited and published in The Federalist, 1/13/19

Tony was a 14-year-old boy who walked into my counseling office with a lot of issues. Short for his age and not yet visibly pubescent, he had been diagnosed with ADHD and his parents felt he might be depressed. He was like hundreds of boys and men I’ve seen in my clinical practice: if the counselor knew how to work with him as a young male, Tony would work with me; if the counselor didn’t, he wouldn’t.

After normal intake, the first thing we did together was walk outside, talking shoulder-to-shoulder. Because the male brain is often cerebellum dependent (it often needs physical movement) in order to connect words to feelings and memories, we sat down only after our walk finished. By then, a great deal had happened for Tony.

Once in our chairs, we talked with a ball in hand, tossing it back and forth, like fathers often do with children. This cerebellum and spatial involvement help the male brain move neuro-transmission between limbic system and frontal lobe (where word centers are). We also used visual images, including video games, to trigger emotion centers, and we discussed manhood and masculinity a great deal, since Tony and every boy yearns for mentoring in the human ontology of how to be a man.

I’ve seen hundreds of girls and women in my therapy practice. Few of them needed walking, physical movement, and visual-spatial stimulation to help access memories, emotions, and feelings because most girls are better able to access words-for-feelings than boys and men while sitting still: girls and women have language centers on both sides of the brain connected to memory, emotion, and sensorial centers while the male brain mainly has these word centers in the left.

Without our realizing it over the last fifty years, we’ve set up counseling and psychological services for girls and women. “Come into my office,” we say kindly. “Sit down. Tell me how you feel/felt.” Boys and men fail out of counseling and therapy because we have not taught our psychologists and therapists about the male and female brain. Only 15% of new counselors are male, leaving 85% female. Clients in therapy skew almost 80% female—males are dragged in by moms or spouses, but generally leave an environment unequipped for the nature of males.

Male nature, the male brain, the need to contextualize boyhood into an important masculine journey to manhood are missing from the new American Psychological Association’s Guidelines for Practice with Boys and Men (www.apa.org/about/policy/boys-men-practice-guidelines.pdf.) While the document calls attention to male developmental needs and crises in our culture, which I celebrate as a researcher and practitioner in the field, it then falls into an ideological swamp.

Males, we are told, are born with dominion created by their inherent privilege; females (and males) are victims of this male privilege. The authors go further to discuss what they see as the main problem facing males—too much masculinity; they call it the root of all or most male issues from suicide to early death to depression to substance abuse to reason for family break ups to school failure to violence. They claim that fewer males than females seek out therapy or stay in therapy and health services because of “masculinity.” Never is the skewed female-friendly mental health environment discussed. The assumption that all systems skew in favor of males, not females, is so deeply entrenched in our culture today, the APA never has to prove it.

Perhaps most worrisome: the APA should be a science-based organization, but its guidelines lack hard science. Ruben and Raquel Gur, Tracey Shors, Louanne Brizendine, Sandra Witelson, Daniel Amen, and the hundreds of scientists worldwide who use brain scan technology to understand male/female brain difference do not appear in the Guidelines. Practitioners like myself and Leonard Sax, M.D., Ph.D., who have conducted multiple studies in science-based practical application of neuroscience to male nurturance in schools, homes, and communities are not included.

Included are mainly socio-psychologists who push the idea that maleness is basically socialized into “masculinities” that destroy male development. Stephanie Pappas on the APA website sums up the APA’s enemy: “Traditional masculinity — marked by stoicism, competitiveness, dominance, and aggression — is, on the whole, harmful.” Our job as therapists is, the authors teach, to remove all but the ideologically sound “masculinities” from boys and men, and specifically remove masculinities that involve competition, aggression, strength, and power.

How much longer can our society and its professionals pretend we are developing a saner society by condemning the very parts of males that help them succeed, heal, and grow? In the same way that it is misogynistic to claim femininity is inherently flawed, it is misandrist to claim that masculinity is also thus.

I am an example: I was a sexual abuse victim in my boyhood, and a very sensitive boy. My ten years of healing from the abuse came as much from tapping into masculine strength as it did by expanding my sense of self in the 1970s toward the feminine. Both are good; neither is zero-sum, but I could not have healed without masculinity.

Part of the problem with the APA guidelines is that, from a neuro-science point of view, masculinity is not as limited as Pappas’ assessment. Masculinity is an amalgam of nature, nurture, and culture. Masculinity—including traditional masculinity–is an ontology in which a male of any race, creed, ethnicity, or kind commits to developing and exercising strength, perseverance, hard work, love, compassion, responsibility for others, service to the disadvantaged, and self-sacrifice.

What professional in the psychology field would not want to embolden these characteristics? Most fathers and mothers would want counselors to embolden them because, despite the APA authors’ lip-service to fathering in the document, fathering and mentoring boys in masculine development has been proven one of the most important determinants in child safety, school success, and emotional and physical health.

Not the erasure of masculinity but the accomplishment of it is required—including inside the counseling office and while walking along the street—if we are to save our sons from the crises outlined in the APA guidelines. Without counselors and parents understanding how to raise and protect masculine development and the male brain, boys like Tony drift in and out of video games, depression, substances, half-love, and, often, violence.

The masculine journey is not perfect and expanding what “masculine” and “man” mean to a given family and self is a point well made by the APA authors and an important one. But trying to hook mental health professionals into the ideological trinity of ideas:

*masculinity is the problem

*males do not need nurturing in male-specific ways because men have it all in our society anyway; and

*manhood is not an ontology, a way of healthy being, but a form of oppression,

ignores one of the primary reasons for the existence of our psychology profession—not just to help girls, women, and everyone on the gender spectrum be empowered and find themselves, but also to help boys and men find their strength, their purpose, and their success in what will be, for them, a complex male journey through an increasing difficult lifespan.

We will discuss this and other topics of depth at our Winter Institute. Please join us! Check out www.gurianinstitute.com to learn more and to register.

Sources

Michael Gurian, How do I Help Him: A Practitioner’s Guide for Working with Boys and Men in Therapeutic Settings (2011) https://www.michaelgurian.com/products/how-do-i-help-him/.

Amen, D.G., et.al., “Women Have More Active Brains Than Men. August 7, 2017 Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. https://www.j-alz.com/content/women-have-more-active-brains-men.

Halpern, D.F., et.al., “The Science of Sex Differences in Science and Mathematics.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest. August 8, 2007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25530726.

Michael Gurian, Saving Our Sons: A New Path to Raising Healthy and Resilient Boys (2017). https://www.michaelgurian.com/products/saving-our-sons/.

Burman, D., et.al., “Sex Differences in Neural Processing of Language Among Children.” March 2007. Neuropsychologia, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.12.021.

Benedict Carey, “Need Therapy: A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” New York Times. May 21,2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/22/health/22therapists.html.

Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Boys and Men

www.apa.org/about/policy/boys-men-practice-guidelines.pdf.

Stephanie Pappas, “APA issues first-ever guidelines for practice with men and boys.” APA Monitor. January 2019. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/01/ce-corner.aspx.

For studies on Fathering, see the Coalition to Create a White House Council on Boys and Men’s meta-study, co-authored by W. Farrell., M. Gurian, M. Nemko, and P. Moore and 34 other scholars, updated, 2017, at http://whitehouseboysmen.org/the-proposal.