With so much schooling online this past year, our homes have naturally adjusted to our children spending five to eight or more hours a day in front of screens. We can say this was (is) a necessity because of Covid 19, and that’s fair. But that much screen time is bad for children’s brains.

There are things we can do to mitigate potential damage, and this blog will look at them with you, from the viewpoint of the female brain. At our Summer Training Institute this summer, Michael Gurian and Eva Dwight will provide insight on this issue, as well as strategies to protect the minds of girls in our digital age. For more about the Summer Training and to register, please click: https://gurianinstitute.com/events/gurian-summer-institute-2021/.

Gail and I (Michael) have two daughters, Gabrielle and Davita. They are 31 and 28 now, but when we were raising them, few things worried us more than their digital health. The digital world they—and we—lived in was a barrage, overwhelming—before we knew it, our children were spending many hours a day staring into screens. As we worked to help our daughters take control of their digital health, they would say, “But you spend 8 to 10 hours in front of screens and you guys seem okay.” It was a good argument in a home that prided itself on constant argument and debate, but we had to respond: “Our brains are fully grown, yours are not. We need to help you protect your brains.”

Our response was, in some ways, a vacuous one, since our adult screen time did have a negative effect on our bodies and brains (both Gail and I could have used a “makeover” of our screen time habits back then), but at the same time, the argument had merit—a child’s brain and an adult’s include different vulnerabilities. Children’s brains are pruning their cells and replacing them with cells that might not, because of digital misuse, be the healthier ones. We needed to make sure our daughters’ brain growth and pruning remained as natural—and, thus, successful—as possible.

Digital Health and Your Daughter

Digital health is a form of mental health. It is the interface of your child’s natural template for brain and physical development with her habits of screen and digital technology use. Digital health will not feel exactly the same to one sister (or brother) as another because use of technology does not have exactly the same effect on every child, but if you ensure digital health in seven stages—the seven stages of major brain development episodes—you can develop a plan of best practices for the digital health of each of your daughters.

Digital health is crucial to a boy’s development, of course, and much of what I saw in this blog post applies to boys, but we will look at girls’ digital health for a moment because there are female/male brain differences at play. Especially in areas of social rumination and resulting anxiety or depression, the female brain is very active, and can be quite vulnerable.

Is digital health a necessity for today’s parents? Is it especially crucial in a Covid and post-Covid world? Yes, yes, and yes, for two primary reasons: frequency and effects.

Regarding frequency, a Pew research study pre-Covid showed 45% of teens online “almost constantly.” That percentage was almost double the number five years ago. Social media use and screen time were already growing in influence on children. Girls outnumbered boys in their use of social media while boys outnumbered girls in their use of video games. During Covid all those number skyrocketed. Now, the majority of teens are online constantly, and even more tweens as well.

Regarding effects: psychologist Jean Twenge, author of I-Gen, in a Wall Street Journal article before Covid, on college age digital life, reported that the internet generation (born since 1995) has “higher rates of anxiety and depression than older millennials.” This finding has been corroborated by the American Pediatric Association, among others. Now, during Covid, multiple studies show multiple increases in anxiety and depression because of lock downs, Covid isolation, and increased digital use.

With increased use of screens and social media come more mental health issues. As a culture, we have become so accustomed to talking about depression and anxiety as commonplace now, we forget that these are brain disorders—they are mental health issues or, put more frankly, forms of mental illness. While there is no reason anymore to stigmatize them, none of us want them for our child. Especially if a child has active depression or anxiety genes, protecting our children from excessive screen time and social media use becomes a way of protecting their brains from illness.

To protect your child, you can become a citizen scientist of digital health. Study your children’s digital practices for two straight weeks. Keep a log or journal. Get your kids to do the same, depending on their age and ability. At the end of two weeks, discuss your family’s findings together and create a plan. This strategy is even more necessary during and post-Covid. We don’t want the pandemic to hurt us even more than it has hurt so many families by increasing anxiety and depression in our girls because of excessive digital use.

Asking the Right Questions, with Your Children

No time is better than a family dinner to train your children to become citizen scientists, too. You can ask and answer, together, the right questions. Here is condensed dialogue from our family’s dinner table conversations and those of other families I’ve worked with.

”Kids, how much screen time do you think is enough screen time for your brain health?”

“Doesn’t it depends on how old I am?”

“You’re right, it does. It can have some pretty negative effects.”

“Adults are always assuming the worst. Aren’t there advantages to screen time and social media?”

“Yes. For instance, research consistently shows that social media can help you build connections with friends.”

“So what’s the problem? Why are you so vigilant about my social media use?”

“It can open you to predators for one thing, but even more subtle, it can make you depressed and anxious because it messes with your brain.”

“How?”

“It creates rumination loops in your brain that are hazardous, it strains your eyes, it keeps you from sleeping, and it creates significant distractability, for starters.”

“So, okay, I need to be protected, but let’s not overdo it.”

“We won’t, and we’ll do this together. For instance, what do you think is the right age for a child to get a Smart Phone?”

“Nine.”

“Good try, but the research says 13 – 14. Let’s read it together (see below).

“But come on—you adults are being negative again. There are lots of advantages of digital time to our brains.”

“Yes, there are. We discussed a couple, but give me more.”

“Social media and the Internet make me smarter, they make me more global, they give me lots of friends, they help me bond with people in the groups I join.”

“That’s all true, and there’s new research showing that white matter activity in your brains is affected, sometimes positively (with more new cells and connections) when you use social media and digital tools.”

“White matter? What’s that?”

“It’s the brain’s connective tissue, its highway system. When you use social media, connections between various brain centers can grow or dissipate, which can have a positive effect on your growth.”

“But? I know you’ve got a ‘But’–“

“But, because new brain cells and connections work both ways—they can also work against you when you get agitated or overreact to something someone does on social media: this can create new cells for anxiety or depression, cells along the highway that connect areas of your brain into ‘rumination loops’ and ‘constant anxious thoughts.’ For instance, a new study out of UNC-Chapel Hill used brain scans to show that adolescents who frequently use social media for ‘digital status seeking’ (any activity where you compare yourself to others via Smart Phones, Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, etc.), can set up a situation where your brain actually starts working against you, not just in increased depression and anxiety, but risky behaviors like substance abuse and risky sex. According to this study, ‘girls who used social media for more than an hour a day at age 10 were found to have the highest risk for developing social and emotional problems at age 15. Can you see now why we want to protect you?”

Seeing a Girl’s Digital Health in Seven Stages

Our family was very “science” oriented when we raised our kids, so our family dinners were often dialogues like the one you just read. Gail and I were constantly giving resources and research to our kids so they could see what was going on in their brains, their psyches, their natural development, and their emotional lives.

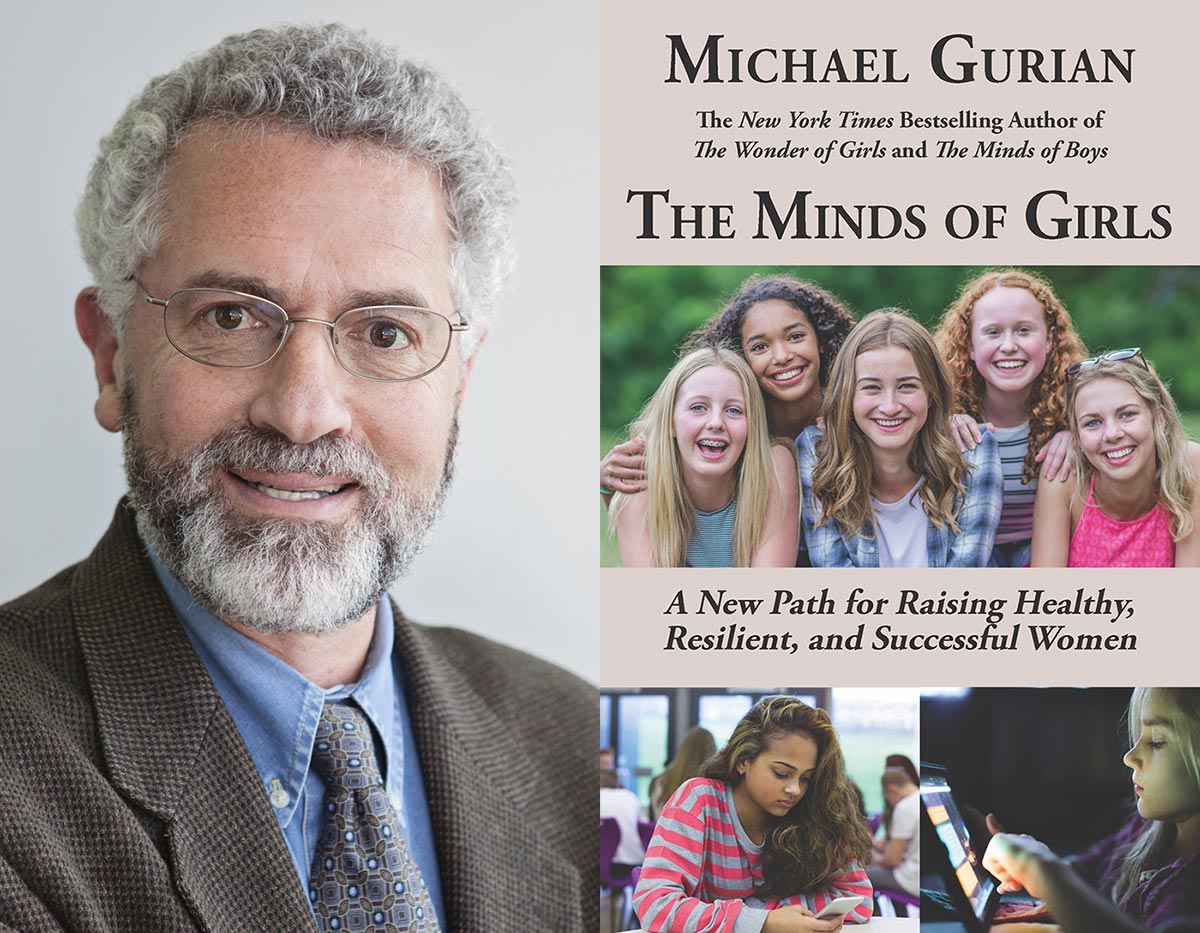

While you might not spend your life doing this kind of research, you can still become a citizen scientist—social media and the Internet are friends of your process. Studies like the ones in this blog post are everywhere. If you have not gotten The Minds of Girls, I hope you will. It gives you access to other discussion starters and research.

A key element of digital health is a girl’s staged brain development. This can be an entry point for discussion with daughters. The female brain matures in seven developmental stages. In these stages, individual gene expression occurs in diverse environments including technological. While characteristics in each of the stages might exist simultaneously, to some extent, each set of essential characteristics peak at different times, so they constitute a neuro-physiologically sequenced journey to mature adulthood.

Because no two girls are exactly alike, this schedule of stages must be adjusted by you for best use. The stages are listed here with tips and suggestions.

Stage 1: Pre-birth to 2 years old. Little or no screen time. If screens are used, just use them for interacting with grandparents or, perhaps, a short, appropriate TV program. TV shows in the vein of Sesame Street are sometimes used with this age group but watch out—the images in them can often move too quickly for digital health of the 1 year old’s brain.

Stage 2: 3 – 5 years old. Some educational programming can work for this age group but no use of phones yet; a short animated movie can be okay, as long as the images don’t move very quickly. No violence is recommended. Watch out for handing your 1- 5 year old kids your cell phone to use for games or other entertainment while you are busy. This is potentially dangerous to the child’s brain.

Stage 3: 6 – 9. Increased use of educational programming, onscreen games, and animated movies. If live action films are used, content should be monitored, especially for sex and violence. No phones should be given to kids yet as their own, even if they have an allowance and can buy one—if a Smart phone is given as a gift by a relative or friend, take it away until later.

Stage 4: 10 – 13. Still no phones until around 13 or 14. If, however, the school is using screens all day for Covid schooling or using Pads, computers, screens for a lot of lessons/classes and sending kids online for homework, other home screen time should be curtailed to almost none since 4 – 6 hours of school time for Covid schooling is already too much screen time for that brain. Watch out for long drives in the car with screens on—audio (radio/music) and conversation are generally better for a child, especially for a child’s brain that already gets too much screen time.

Stage 5: 14 – 17. Cell phones now, but privacy settings are for parents to set; trust the child but be vigilant; keep screen time to four hours a day if possible; everything else that is healthy should come before home-screen time, e.g. chores, relationships, athletics, exercise, play, and nature time.

Stage 6: 18 – 21 and Stage 7: 22 – 25 and beyond. By the time your daughter is 18, you will have very little control over screen time, but your mentoring is still essential, including presentation to your daughter of new research as it comes out.

If you think your daughter is screen-addicted, it is generally essential that you help her get help before she fully enters adulthood.

Snapshot: a Family Debate about Smart Phones at 13 –14

After a lecture, a mom, Andrea, said, “My daughter, Danielle, is always looking at her phone. How do I get her to stop?”

“How old is she?” I asked immediately.

“Eleven,” Andrea responded quickly and my answer came just as fast.

“Take the phone away from her. Don’t give it back until she is 13 or 14.”

Andrea’s face showed both surprise and suspicion, surprise that my response was so immediate and suspicion that I didn’t understand her plight. “I don’t think I can do that,” she said.

“Why not?” I asked. “It’s your phone, right? It’s not technically your daughter’s. All the devices in your home are the parents’”

“It is,” she agreed. “It is, yes, but—“ she paused, thinking about it, almost physically fidgeting her body to try to wear the idea around. “Well, it is,” she repeated, feeling better about it, “they are.”

“Yes,” I encouraged. “Her attention to the Smart Phone at 11 is actually harming her brain development. Her dopamine (reward) system in her brain is likely becoming compromised; her brain is getting attached to instant gratification in a way that is unhealthy; she is likely creating relational rumination loops in large quantity before her brain is mature enough to filter through them; she is likely status seeking through digital apps before she is mature enough to understand status and identity in these mature ways; she is more likely to get involved in substance abuse…the list is very long and there is no solution except to take the phone away until her brain is ready for it.”

“But maybe what you’re saying won’t apply to Danielle.” [Recently, another comment I have heard in doing my parent talks on zoom is: “But my daughter needs the phone for school and school work.”]

“That’s true,” I said, “but there is likelihood some part of it will, and damage will be done.” [“There are other devices available for school work, like Pads and computers that can be more easily turned on and off when school work is done.]

When Andrea walked away, I believe she felt resolved in taking the phone away, but I don’t know. For tweens, once the phone is given, it is tumultuous to take it away.

Yet with other parents I have heard, “I took it away and I thought life would become terrible but, you know, after a few days, my daughter ended up thanking me. She said, ‘Mom, I have a life now…I’m not addicted to that phone.’”

This is the outcome we hope for, and it is one I have been hearing during this Covid year, as well. More and more parents are getting worried about the excessive screen time and retaining Pads and computers for schoolwork but being much more careful with phones. This is a very good thing for these brains, our children, who are 13 and younger, with especially vulnerable brains in the tween years, brains that are pruning cells constantly.

The Trinity of Digital Health

When you are trying to decide what is best course regarding digital childhood and screen use, there is a trinity of health categories to study: cognitive, physical, social-emotional. If your own daughter is having difficulty in any of these three areas (worsening grades or lack of cognitive function, becoming obese or not getting enough exercise, relational difficulties with adults and/or peers), screen time and social media use can be a culprit. She may be spending so much time on the phone (and with other screen-media) she is becoming:

*too sedentary (a recent study showed that 19 year old girls today are sitting as much as people in their 60s, with increases in this outcome during Covid);

*distracted from academic performance and cognitive development by digital and screen time; and/or

*engaging in too much immature relational activity through digital life to remain socially healthy. During Covid, screens have been an easy way to remain socially active, and that social activity is crucial for children’s maturation and for their happiness, but it also backfires.

Be a citizen scientist and study these elements of your daughter’s life for 2 to 4 weeks. As you gather data, talk in your family, engage your kids, engage teachers and schools, and engage extended family members. Develop your own plan for managing digital health that supports cognitive, physical, and social-emotional growth and success.

Seven Brain-Friendly Strategies

As you gather your research, you may get to the point that Gail and I did, where you see both the need of screens in your daughter’s life but also the drawbacks. To try to gradually get control of screen use, try these seven strategies. Some of these strategies are healthy for us adults, too.

- No screens, including phones, at the dinner table or breakfast table.

- No screens in the child’s room one hour before bedtime—a reading device, like Kindle, that is not-attached to Internet may be an exception to this rule, but not if your child is having difficulty sleeping.

- If your daughter is ruminating, over-reacting, becoming hostile, or abusing substances, take away all screens except educational options for one month, at least.

- After school, screens are used AFTER a child has spent time exercising and/or spending time in nature.

- For teachers: less irrelevant homework will help children spend less time on screens.

- Teach other families and community members the link between screen time, social media, Smart Phones, and depression and anxiety.

- Customize all of the research to YOUR child. If your child shows no difficulties in the trinity of digital health, you may be able to spend less time worrying over your child’s screen time and social media use.

Overall, everyone raising daughters is raising a female brain to succeed at love, wisdom, work, and family. Digital health is brain health. It is on brain health that your daughter’s future depends.

–Michael Gurian

Notes

For varied and in-depth analysis of this topic, please see The Minds of Girls (2018), by Michael Gurian, especially Chapter 7 and the Endnotes.

Abby Ohlheiser, “Teens Are Online More and Are Unsure of the Impact,” The Washington Post, June 2, 2018.

Jean Twenge, I-Gen. New York: Atria. 2017

Emily Esfahani Smith, “A Movement Rises to Take Back Higher Education,” The Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2018

Jennifer Breheny Wallace, “The Teenage Social-Media Trap,” The Wall Street Journal, May 5, 2018.

Nesi, Jacqueline, et.al., “In Search of Likes,” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, April 2018

Susan Pinker, “New Skills Build New Brain Architecture,” The Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2018.

Andrea Peterson, On Edge. New York: Crown. 2017

Gregory Jantz, Healing Depression Forever. Seattle: The Center. 2018

Renee S. Sherrell and Glenn W. Lambie, “The Contribution of Attachment and Social Media Practices to Relationship Development,” Journal of Counseling and Development, July 2018, Vol 96.